Menlo Ventures was founded in 1976 but it took 35 years for the venture capital firm to hit the jackpot.

Since the dot-com boom, Menlo Ventures has teetered between good and great. A prolific Silicon Valley investor, it’s never quite reached the heights of Accel or Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), or established the level of name recognition as Benchmark or Sequoia, firms that struck gold with bets on Facebook, Instagram and Snap.

But where others missed the boat entirely on one of the most valuable tech startups of all time, Menlo Ventures gnawed its way into an early deal at the last possible moment.

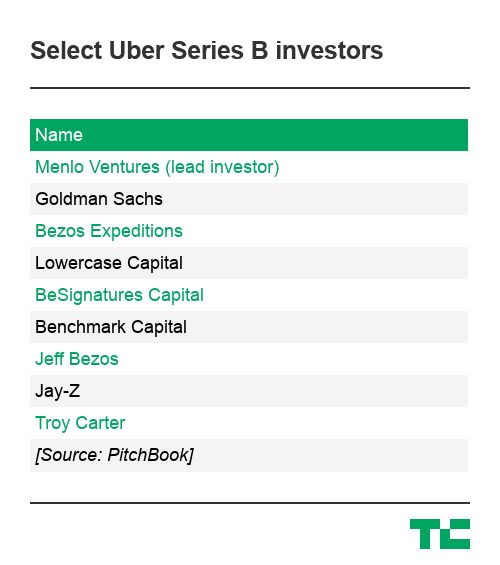

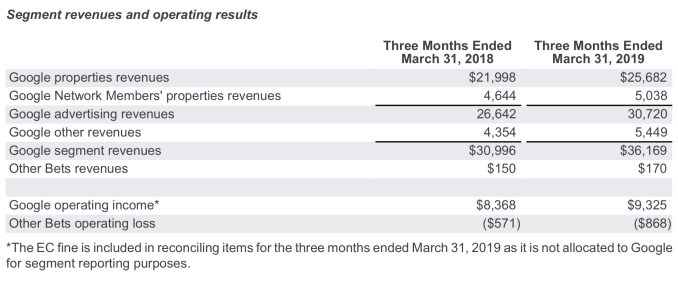

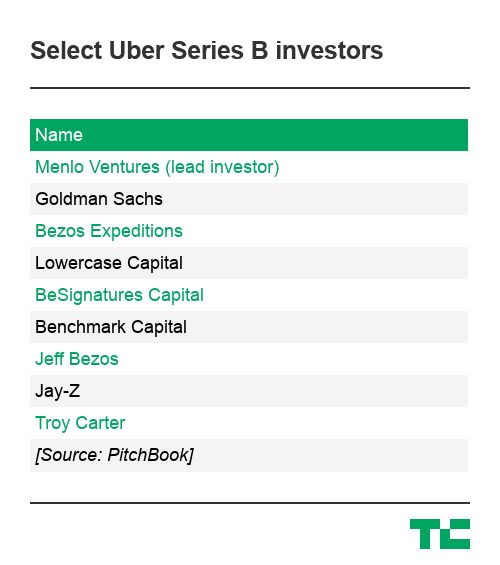

In 2011, the firm led a $32 million Series B funding in a fledgling on-demand car service called Uber, agreeing to value the startup at a colossal $322 million after the company’s first-choice investor, a16z, failed to accept Uber’s sky-high terms. Menlo would go on to invest a total of $66.5 million in the company on expected total returns of up to $3.1 billion.

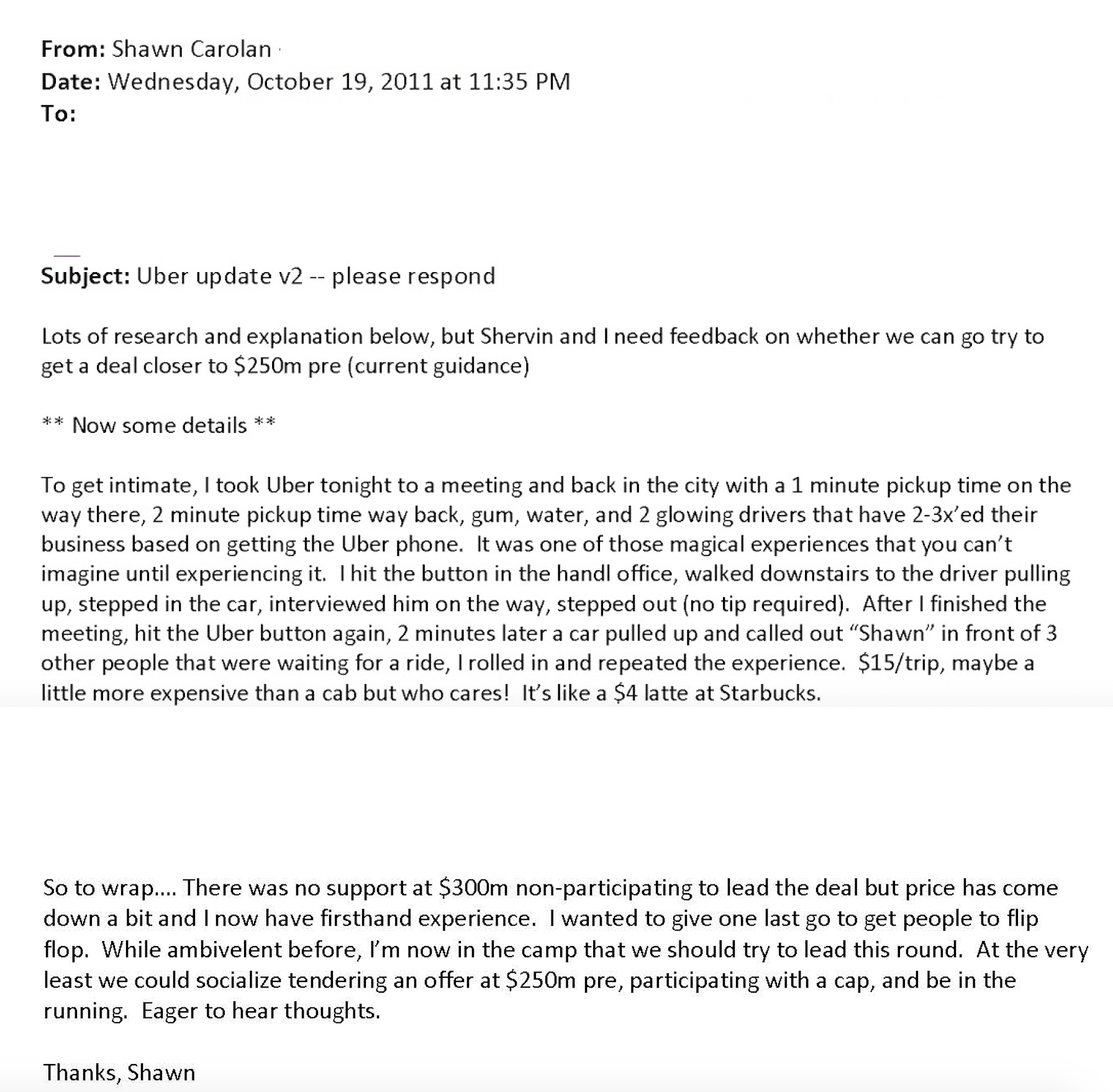

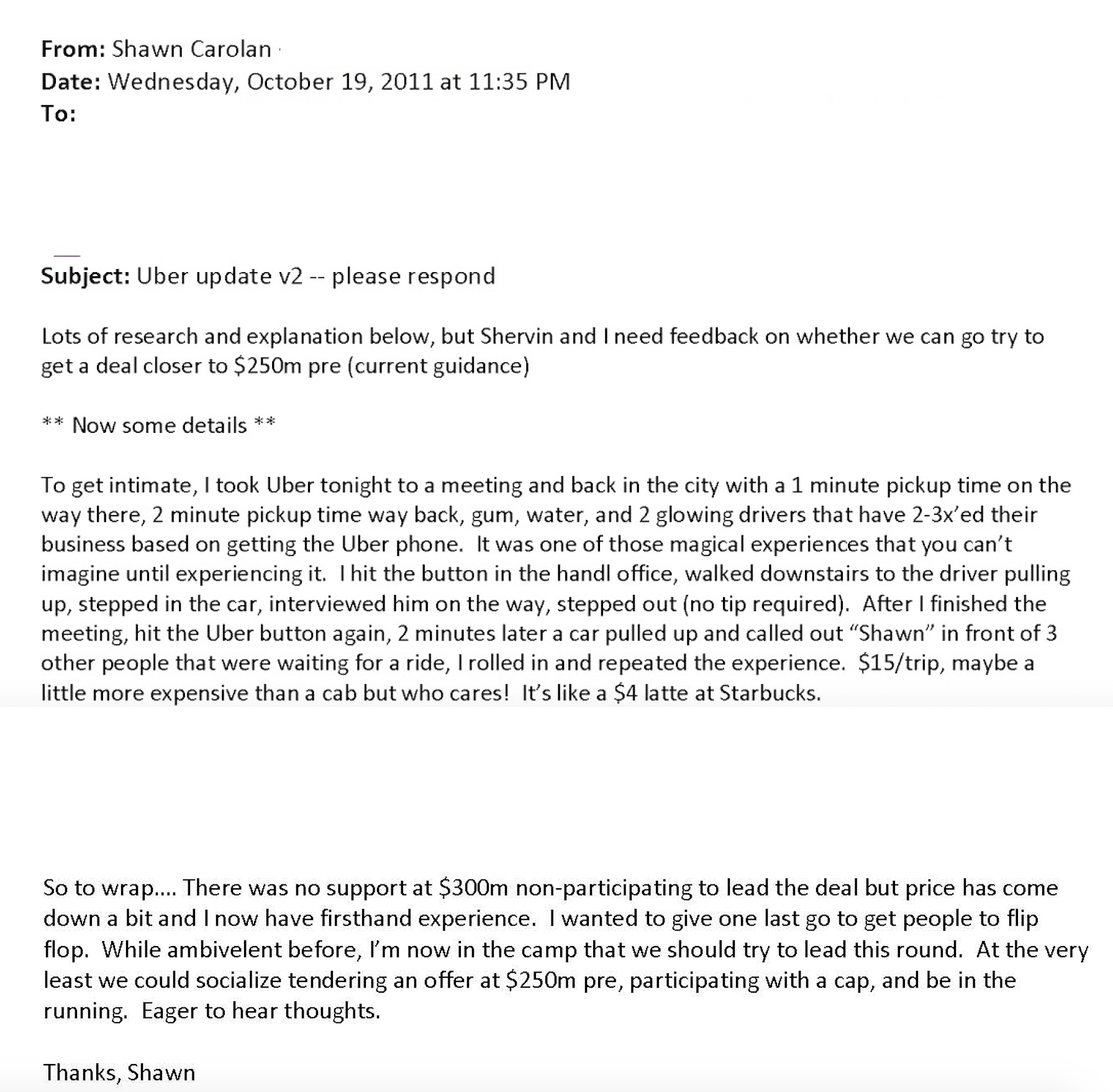

“I wouldn’t have dared to dream quite this big,” Menlo Ventures partner Shawn Carolan told TechCrunch. Carolan and embattled investor Shervin Pishevar, the former Menlo Ventures partner and founder of Sherpa Capital accused of sexual misconduct, secured Menlo a spot on Uber’s cap table years ago when several firms were vying for a stake.

The pair, according to discussions with insiders, are polar opposites, representatives of the diverging approaches to deal-making in Silicon Valley. While Pishevar, described to TechCrunch as “overpowering” and “self-promotional,” developed a lasting relationship with Uber co-founder and former chief executive officer Travis Kalanick crucial to the deal, Carolan, a reserved Midwesterner, crunched the numbers and worked to convince his firm that Uber, a young startup with a hot-headed leader, was worth their time and money.

Now, as Uber preps for an imminent initial public offering, the firm wants to shine a light on Carolan, an under-the-radar investor known more for his humility than his portfolio.

Menlo Ventures partner Shawn Carolan’s last-ditch effort to convince his firm to invest in Uber in late 2011.

A historic IPO

As Uber approaches its IPO, a slew of investors that were in the right place at the right time await a payday of unforeseen scale.

Uber dropped its IPO prospectus in early April. Next week, it’s expected to debut on the New York Stock Exchange at a valuation between $80 billion and $100 billion, up from its most recent private valuation of $72 billion. The IPO will be amidst the largest liquidity events for a U.S. VC-backed technology company in history, on par with Facebook’s 2012 public offering that valued the social media empire at $104 billion.

In addition to Menlo Ventures, the Japanese telecom giant SoftBank, Benchmark, Uber co-founders Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and GV, the investment arm of Alphabet, own stakes in Uber worth billions.

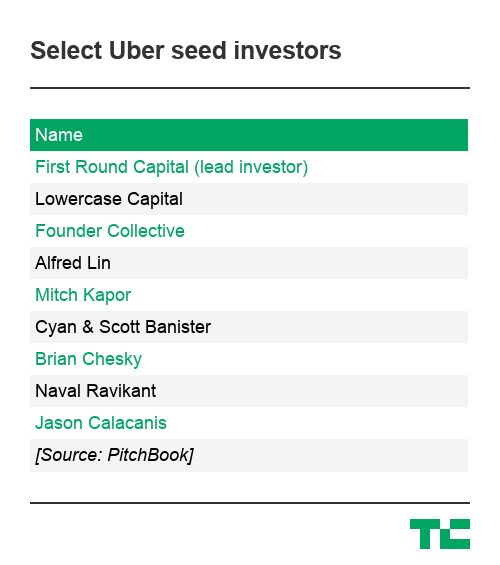

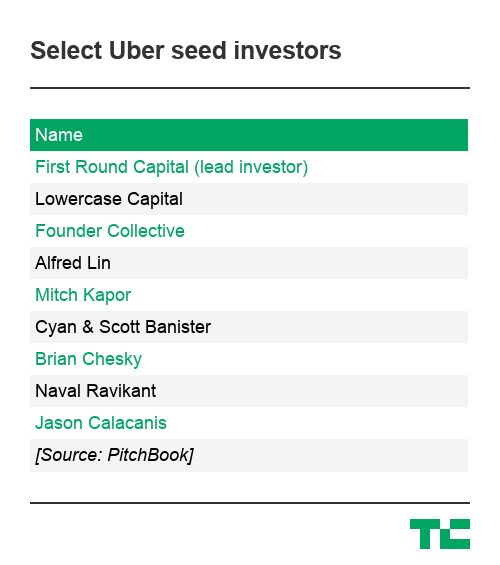

Seed backers like Chris Sacca of Lowercase Capital and Rob Hayes of First Round Capital, who invested in “UberCab” before it had anything to show for itself, will also earn tremendous payouts.

Menlo has already raked in hundreds of millions in profits from its Uber investment, as have several other investors that sold their shares on the secondary market. In 2018, Menlo earned $973 million when a group of investors led by SoftBank purchased nearly half of its Uber stock. The deal represented a 93x return on shares the firm had paid $10.5 million for years prior, according to the firm’s calculations.

Since that transaction, Menlo has expanded its Uber stake through the sale of its portfolio company Jump Bikes to Uber in 2018. The firm had invested $7.5 million in Jump, a provider of a dockless bicycle system, only months before it was acquired by Uber for $200 million. Menlo, as a result, banked another $50 million in Uber stock.

Today, it owns a 2.3 percent stake in Uber worth between $1.85 billion and $2.1 billion, depending on how Uber prices its IPO.

Beers and a term sheet

Uber founding CEO Travis Kalanick.

The story of Menlo Ventures’ investment in Uber dates back to 2005 when Carolan first met Travis Kalanick, Uber’s founder and former chief executive. The notorious entrepreneur was fundraising for an earlier company, a peer-to-peer file-sharing startup called Red Swoosh. Menlo didn’t invest, but Kalanick left a lasting impression.

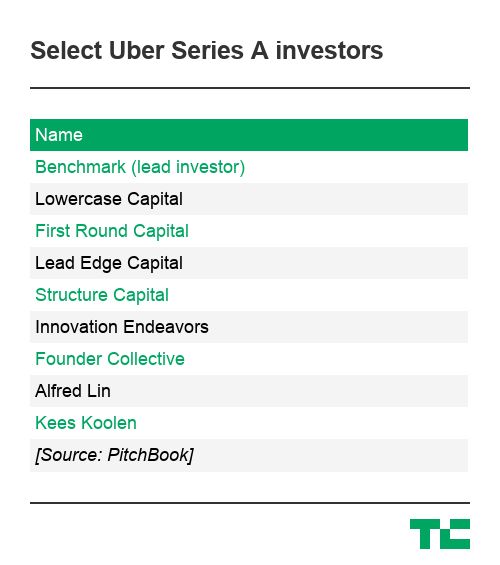

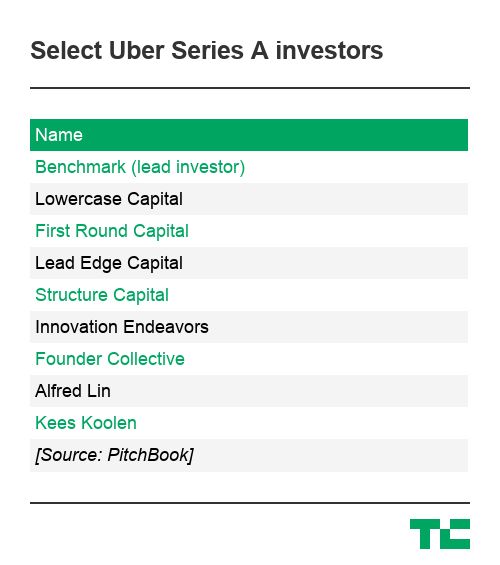

Years later, Benchmark general partner Matt Cohler called Pishevar on his cell phone to let him know Uber had begun raising its Series B. Pishevar didn’t know Kalanick yet but had been introduced to his fast-growing car-sharing business by AngelList founder and Uber backer Naval Ravikant in 2010.

Pishevar was a garish type who would two years later leave Menlo to launch his own firm Sherpa Capital, a backer of Slack, Airbnb, Robinhood, Hyperloop One and more. Carolan was restrained, focused more on metrics than relationships. Together, the pair worked their way onto Uber’s cap table with Pishever serving as the lead investor externally and internally, both men receiving credit as leads.

Venture capitalists often brag about the skill required to land the best deals, but most of the time, it comes down to luck and timing. Menlo, in this case, got really lucky.

A recent feature on Andreessen Horowitz in Forbes detailed the firm’s biggest misstep: losing Uber. Hours before they were set to sign a term sheet, the firm shifted, offering Uber a lower valuation than what had been promised. Kalanick, known already at that point for his disdain for investors, walked. Little did the Menlo team know they were being used as a “stalking horse for leverage,” according to Forbes’ reporting. So when a16z tried to cheapen the deal, Uber turned immediately to its second-choice, Menlo Ventures.

A16z declined to provide additional details for this story.

“Whenever you have a company of this caliber that has that kind of growth rate, there’s a lot of people that are vying for the opportunity to invest,” Carolan said. “Frankly, there’s never been a company like Uber.”

With a sense of urgency, Pishevar hopped on a plane to Dublin, Ireland at Kalanick’s request. The CEO was speaking at a technology conference called Web Summit. It was there that the term sheets were signed over pints at the Shelbourne Hotel, and a close friendship between Pishevar and Kalanick would begin to blossom. Pishevar, according to The New York Times, later introduced the ride-hail chief to the club scene and Los Angeles celebrity culture. Until Kalanick’s final days as CEO, Pishevar would fiercely defend the founder’s dog-eat-dog style of management. To this day, the two are close friends.

Meanwhile, Carolan was heads down, benchmarking Uber against other tech companies, completing a thorough unit economics analysis and hoping his colleagues wouldn’t be disappointed by the Uber investment, a point of contention among certain Menlo staffers who viewed Uber as a limo dispatch company with an app, not the next billion-dollar business.

“There were a lot of things you had to believe back then and at that moment in time, Uber didn’t paint that picture, [Carolan] was the one who painted that picture,” Mark Siegel, a managing director at Menlo since 1996, told TechCrunch. “And he pounded the table pretty hard.”

After all, Uber was only active in four markets at the time of Menlo’s initial investment: San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago and New York City. Rider bookings were growing fast but were just $1 million per month, with close to zero net revenue after paying drivers. Carolan himself was unconvinced of the business’s longevity until his first ride in an Uber turned him.

Uber declined to confirm early booking figures.

“We had a lot of heartburn over the valuation,” Carolan said. “But it’s the ones you don’t chase, like YouTube, which I kind of dismissed as a lousy business and didn’t chase it. When you see something like Uber that has that type of repeated retention and essentially zero customer acquisition, it’s kind of like, okay, this is just a magical experience that’s going to sell itself.”

Carolan’s commitment was recognized internally but while Uber gained momentum, so did Pishevar. His involvement in Uber brought him notoriety, while Carolan’s role slipped through the cracks. Even when accusations of sexual misconduct against Pishevar surfaced in 2017, his name was often preceded by “early Uber investor.”

Pishevar was accused of sexually harassing multiple women, including Uber’s very own former head of global expansion, Austin Geidt. The Bloomberg expose highlighting allegations against him came just one month after a report he had been arrested in London for rape. Charges for the reported London incident were later dropped and Pishevar, through his lawyer, has said the other claims were part of a “smear campaign” against him.

Menlo Ventures sought to distance itself from the scandal, naturally, claiming in a series of tweets they had no knowledge of inappropriate behavior during his tenure at the firm.

A self-effacing venture capitalist

A Chicago native, Shawn Carolan joined Menlo Ventures in 2002 as a 28-year-old fresh out of Stanford’s business school. His wife and high school sweetheart, Jennifer Carolan, would make a career as a venture capitalist, too, co-founding Reach Capital, an edtech-focused VC fund coincidentally located next door to Menlo’s San Francisco outpost.

Menlo Ventures partner Shawn Carolan.

In 2009, the Menlo team realized they had overcompensated on enterprise and made the call to pioneer a reinvigorated consumer tech strategy spearheaded largely by Carolan.

In 2011, to bolster the new effort, Carolan hired Pishevar, a rookie VC they hoped would bring a fresh perspective to a firm of engineering geeks. Immediately, Pishevar sourced Square, Jack Dorsey’s hot new payments startup. The team rallied behind him but ultimately, Square went with Kleiner Perkins’s Mary Meeker instead. Later, Pishevar would bring in Pinterest and Snap, mere months after the ephemeral messaging app had launched but the Menlo team passed, according to a source with knowledge of the deals.

In Pishevar’s first six months at Menlo, he invested in Tumblr, Warby Parker, Machine Zone and Uber.

Carolan, for his part, has returned more capital in a single year than any partner in its history, the firm said. In a 12-month period between 2017 to 2018, Roku’s IPO and the Uber stock sale brought in some $2 billion in returns for Menlo, capital that was used to fuel its latest fund, a $500 million vehicle focused on Series B and C-stage startups.

In addition to accumulating a 35.3 percent pre-IPO stake in the digital streaming business Roku, which the firm celebrated with boxes of popcorn implanted with several thousand dollars in cash bonuses for the administrative team, Carolan was the first institutional investor in Siri, the personal assistant application Apple paid a little more than $200 million for in 2010. More recently, he invested in Chime, a mobile banking platform valued at $1.5 billion in March.

Pishevar, since leaving Menlo, has continued to ink deals with high-flying unicorns, including Uber, in which Sherpa invested an additional $200 million. However, since resigning from Sherpa Capital following the sexual misconduct scandal in 2017, he’s kept a much lower profile. Most recently, he signed on as an investor and board member at Bolt Mobility, an electric scooter business in Florida. A 2018 Florida business filing listed him as the company’s sole officer, though the Bolt team recently told BuzzFeed Pishevar was strictly an investor. The Sherpa Capital team, for their part, have relaunched as ACME Capital.

Bolt has not responded to a request for comment.

An implosion

Menlo remained one of the largest institutional backers in Uber for years, a position that, while lucrative, proved tricky when Uber began to unravel internally.

When Pishevar left Menlo Ventures to build Sherpa Capital in 2013, Carolan assumed the Menlo board observer seat for the next 21 months. Pishevar, now a close friend to Kalanick, stayed on the board as an observer until 2015.

Eventually, Carolan would take a step back from Menlo to focus on his productivity startup, Handle. But when Handle failed to become the rocket ship Carolan had dreamed of, he returned to investing at Menlo full-time with a newfound empathy for founders.

Little did he know he would play a role in the high-profile ouster of one of the most notable tech founders of all time.

In July 2016, talks of Kalanick’s resignation led by Benchmark general partner and Uber board member Bill Gurley began. Menlo had given up its board observer seat by then, but was part of a consortium of four key early Uber investors (Benchmark, First Round Capital and Lowercase Capital) that controlled the preferred share vote, which was needed to make impactful decisions; for example, approving new board seats or remove a founding CEO.

In 2017, it became abundantly clear that Uber would never achieve profitability nor complete its highly anticipated IPO with Kalanick at the helm. Susan Fowler had published her infamous blog post, executives were quitting, remarks on Uber’s toxic culture could be found just about anywhere and the #DeleteUber campaign had turned social media against the ride-hail company.

Shervin Pishevar (right) looks on as he gives a press conference during the Web Summit at Parque das Nacoes, in Lisbon on November 10, 2016. (PATRICIA DE MELO MOREIRA/AFP/Getty Images)

Uber was going to implode if the board didn’t act. Benchmark’s Gurley took center stage, calling on Kalanick to resign. Pishevar remained a Kalanick confidant and later when Benchmark sued Kalanick, he published a bizarre open letter in an eleventh-hour attempt to sway the public to rally behind the ousted CEO. Carolan, reluctant to be perceived as anything other than founder friendly, turned against the founder and advocated alongside Gurley for Kalanick’s removal.

“I imagine he wouldn’t be particularly happy with me for having done that but you gotta do what you gotta do sometimes,” Carolan said. “Ultimately, our job is to help that company achieve its mission. It’s not an allegiance to any one person at the company.”

Finally, Kalanick gave up the Uber C-suite in June 2017 and former Expedia Group CEO Dara Khosrowshahi stepped in as his replacement. Sixteen months later, Uber would file confidentially for a 2019 IPO.

A lasting impact

Menlo Ventures leaped into cutting-edge consumer investing at a time when its reputation in The Valley was unremarkable. For years, decades even, the firm shielded itself from PR and declined to take the spotlight as the Andreessen Horowitzes of the world touted their successes.

Today, the firm is more accepting of attention, leveraging its Uber position to attract entrepreneurs and foster new unicorns, like the more recent portfolio additions Chime and Carta.

“It has clearly benefited us in terms of the overall perception of the firm and credibility,” Siegel said, admitting he was one of the Menlo partners dubious of its 2011 Uber investment. “There’s no doubt it has been a huge positive.”

In the years since Uber came along, Menlo has made key additions to its team, marking the beginning of a new era for the timeworn investor. In 2015, it hired Steve Sloane, who became the firm’s youngest partner to date when he was promoted earlier this year. Naomi Ionita, the firm’s only female partner, joined in early 2018. And Grace Ge, a fresh recruit from RRE Ventures in New York, started this week as a senior associate on the venture team. Another yet-to-be-announced hire will begin in June.

Uber, despite narrowly avoiding a complete implosion in 2017, has changed the game for many investors. The returns it will generate in the next several months will refresh the coffers of many venture capital funds. Money tied to Uber will flow toward the next generation of founders for years to come, and the investors responsible for its landmark success will boast about it for the remainder of their careers.

Even if Uber doesn’t turn out to be the Wall Street darling its investors hope — Lyft has struggled to accumulate value on the public markets — the company has indisputably transformed the Silicon Valley playbook for hypergrowth and execution in the gig-economy ecosystem.