Last night’s episode of “Game of Thrones” was a wild ride and inarguably one of an epic show’s more epic moments — if you could see it through the dark and the blotchy video. It turns out even one of the most expensive and meticulously produced shows in history can fall prey to the scourge of low quality streaming and bad TV settings.

The good news is this episode is going to look amazing on Blu-ray or potentially in future, better streams and downloads. The bad news is that millions of people already had to see it in a way its creators surely lament. You deserve to know why this was the case. I’ll be simplifying a bit here because this topic is immensely complex, but here’s what you should know.

(By the way, I can’t entirely avoid spoilers, but I’ll try to stay away from anything significant in words or images.)

It was clear from the opening shots in last night’s episode, “The Longest Night,” that this was going to be a dark one. The army of the dead faces off against the allied living forces in the darkness, made darker by a bespoke storm brought in by, shall we say, a Mr. N.K., to further demoralize the good guys.

Thematically and cinematographically, setting this chaotic, sprawling battle at night is a powerful creative choice and a valid one, and I don’t question the showrunners, director, and so on for it. But technically speaking, setting this battle at night, and in fog, is just about the absolute worst case scenario for the medium this show is native to: streaming home video. Here’s why.

Compression factor

Video has to be compressed in order to be sent efficiently over the internet, and although we’ve made enormous strides in video compression and the bandwidth available to most homes, there are still fundamental limits.

The master video that HBO put together from the actual footage, FX, and color work that goes into making a piece of modern media would be huge: hundreds of gigabytes if not terabytes. That’s because the master has to include all the information on every pixel in every frame, no exceptions.

Imagine if you tried to “stream” a terabyte-sized TV episode. You’d have to be able to download upwards of 200 megabytes per second for the full 80 minutes of this one. Few people in the world have that kind of connection — it would basically never stop buffering. Even 20 megabytes per second is asking too much by a long shot. 2 is doable — slightly under the 25 megabit speed (that’s bits… divide by 8 to get bytes) we use to define broadband download speeds.

So how do you turn a large file into a small one? Compression — we’ve been doing it for a long time, and video, though different from other types of data in some ways, is still just a bunch of zeroes and ones. In fact it’s especially susceptible to strong compression because of how one video frame is usually very similar to the last and the next one. There are all kinds of shortcuts you can take that reduce the file size immensely without noticeably impacting the quality of the video. These compression and decompression techniques fit into a system called a “codec.”

But there are exceptions to that, and one of them has to do with how compression handles color and brightness. Basically, when the image is very dark, it can’t display color very well.

The color of winter

Think about it like this: There are only so many ways to describe colors in a few words. If you have one word you can say red, or maybe ochre or vermilion depending on your interlocutor’s vocabulary. But if you have two words you can say dark red, darker red, reddish black, and so on. The codec has a limited vocabulary as well, though its “words” are the numbers of bits it can use to describe a pixel.

This lets it succinctly describe a huge array of colors with very little data by saying, this pixel has this bit value of color, this much brightness, and so on. (I didn’t originally want to get into this, but this is what people are talking about when they say bit depth, or even “highest quality pixels.”)

But this also means that there are only so many gradations of color and brightness it can show. Going from a very dark grey to a slightly lighter grey, it might be able to pick 5 intermediate shades. That’s perfectly fine if it’s just on the hem of a dress in the corner of the image. But what if the whole image is limited to that small selection of shades?

Then you get what we see last night. See how Jon (I think) is made up almost entirely of only a handful of different colors (brightnesses of a similar color, really) in with big obvious borders between them?

Then you get what we see last night. See how Jon (I think) is made up almost entirely of only a handful of different colors (brightnesses of a similar color, really) in with big obvious borders between them?

This issue is called “banding,” and it’s hard not to notice once you see how it works. Images on video can be incredibly detailed, but places where there are subtle changes in color — often a clear sky or some other large but mild gradient — will render in large stripes as the codec goes from “darkest dark blue” to “darker dark blue” to “dark blue,” with no “medium darker dark blue” in between.

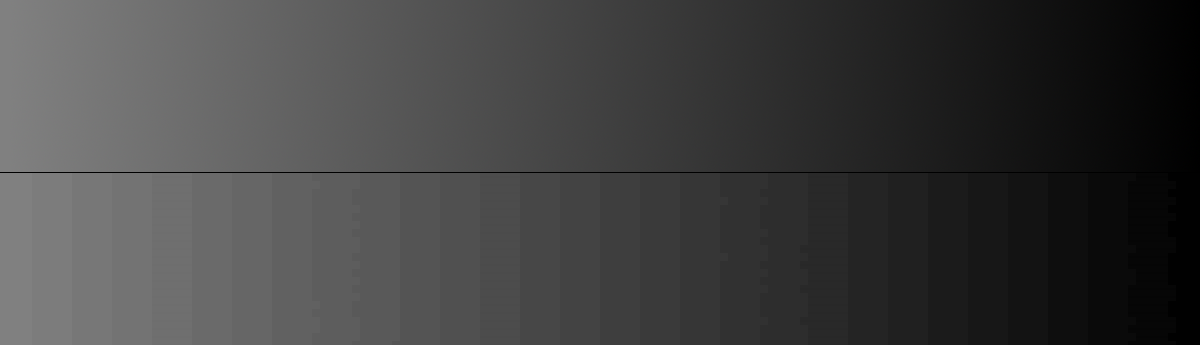

Check out this image.

Above is a smooth gradient encoded with high color depth. Below that is the same gradient encoded with lossy JPEG encoding — different from what HBO used, obviously, but you get the idea.

Above is a smooth gradient encoded with high color depth. Below that is the same gradient encoded with lossy JPEG encoding — different from what HBO used, obviously, but you get the idea.

Banding has plagued streaming video forever, and it’s hard to avoid even in major productions — it’s just a side effect of representing color digitally. It’s especially distracting because obviously our eyes don’t have that limitation. A high-definition screen may actually show more detail than your eyes can discern from couch distance, but color issues? Our visual systems flag them like crazy. You can minimize it in various ways, but it’s always going to be there, until the point when we have as many shades of grey as we have pixels on the screen.

So back to last night’s episode. Practically the entire show took place at night, which removes about 3/4 of the codec’s brightness-color combos right there. It also wasn’t a particularly colorful episode, a directorial or photographic choice that highlighted things like flames and blood, but further limited the ability to digitally represent what was on screen.

It wouldn’t be too bad if the background was black and people were lit well so they popped out, though. The last straw was the introduction of the cloud, fog, or blizzard, whatever you want to call it. This kept the brightness of the background just high enough that the codec had to represent it with one of its handful of dark greys, and the subtle movements of fog and smoke came out as blotchy messes (often called “compression artifacts” as well) as the compression desperately tried to pick what shade was best for a group of pixels.

Just brightening it doesn’t fix things, either — because the detail is already crushed into a narrow range of values, you just get a bandy image that never gets completely black, making it look washed out, as you see here:

(Anyway, the darkness is a stylistic choice. You may not agree with it, but that’s how it’s supposed to look and messing with it beyond making the darkest details visible could be counterproductive.)

Now, it should be said that compression doesn’t have to be this bad. For one thing, the more data it is allowed to use, the more gradations it can describe, and the less severe the banding. It’s also possible (though I’m not sure where it’s actually done) to repurpose the rest of the codec’s “vocabulary” to describe a scene where its other color options are limited. That way the full bandwidth can be used to describe a nearly monochromatic scene even though strictly speaking it should be only using a fraction of it.

But neither of these are likely an option for HBO: Increasing the bandwidth of the stream is costly, since this is being sent out to tens of millions of people — a bitrate increase big enough to change the quality would also massively swell their data costs. When you’re distributing to that many people, that also introduces the risk of hated buffering or errors in playback, which are obviously a big no-no. It’s even possible that HBO lowered the bitrate because of network limitations — “Game of Thrones” really is stretching the limits of digital distribution in some ways.

And using an exotic codec might not be possible because only commonly used commercial ones are really capable of being applied at scale. Kind of like how we try to use standard parts for cars and computers.

This episode almost certainly looked fantastic in the mastering room and FX studios, where they not only had carefully calibrated monitors with which to view it but also were working with brighter footage (it would be darkened to taste by the colorist later) and less or no compression. They might not even have seen the “final” version that fans “enjoyed.”

We’ll see the better copy eventually, but in the meantime the choice of darkness, fog, and furious action meant the episode was going to be a muddy, glitchy mess on home TVs.

And while we’re on the topic…

You mean my TV isn’t the problem?

Well… to be honest, it might be that too. What I can tell you is that simply having a “better” TV by specs, such as 4K or a higher refresh rate or whatever, would make almost no difference in this case. Even built-in de-noising and de-banding algorithms would be hard pressed to make sense of “The Long Night.” And one of the best new display technologies, OLED, might even make it look worse! Its “true blacks” are much darker than an LCD’s backlit blacks, so the jump to the darkest grey could appear more jarring.

That said, it’s certainly possible that your TV is also set up poorly. Those of us sensitive to this kind of thing spend forever fiddling with settings and getting everything just right for exactly this kind of situation. There are dozens of us! And this is our hour.

Usually “calibration” is actually a pretty simple process of making sure your TV isn’t on the absolute worst settings, which unfortunately many are out of the box. Here’s a very basic three-point guide to “calibrating” your TV:

- Turn off anything with a special name in the “picture” or “video” menu, like “TrueMotion,” “Dynamic motion,” “Cinema mode,” any stuff like that. Most of these make things look worse, and so-called “smart” features are often anything but. Especially anything that “smooths” motion — turn those off first and never ever turn them on again. Note: Don’t mess with brightness, gamma, color space, pretty much anything with a number you can change.

- Figure out light and color by putting on a good, well-shot movie the way you normally do. While it’s playing, click through any color presets your TV has. These are often things like “natural,” “game,” “cinema,” “calibrated,” and so on, and take effect right away. Some may make the image look too green, or too dark, or whatever. Play around with it and whichever makes it look best, just use that one. You can always change it again later – I myself switch between a lighter and darker scheme depending on time of day and content.

- Don’t worry about HDR, dynamic lighting, and all that stuff for now. There’s a lot of hype about these technologies and they are still in their infancy. Few will work out of the box and the gains may or may not be worth it. The truth is a well shot movie from the ’60s or ’70s can look just as good today as a “high dynamic range” show shot on the latest 8K digital cinema rig. Just focus on making sure the image isn’t being actively interfered with by your TV and you’ll be fine.

Unfortunately none of these things will make “The Long Night” look any better until HBO releases a new version of it. Those ugly bands and artifacts are baked right in. But if you have to blame anyone, blame the streaming infrastructure that wasn’t prepared for a show taking risks in its presentation, risks I would characterize as bold and well executed, unlike the writing in the show lately. Oops, sorry, couldn’t help myself.

If you really want to experience this show the way it was intended, the fanciest TV in the world wouldn’t have helped last night, though when the Blu-ray comes out you’ll be in for a treat. But here’s hoping the next big battle takes place in broad daylight.

No comments:

Post a Comment