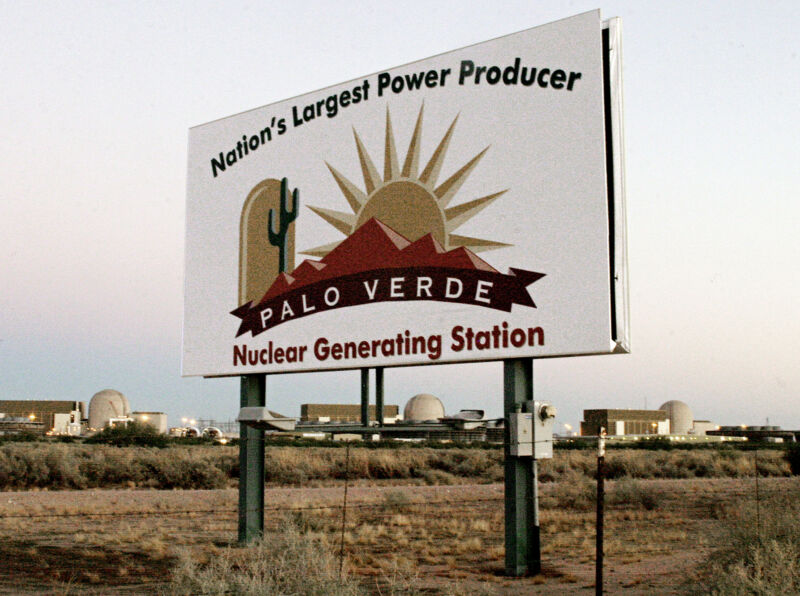

Enlarge / The Palo Verde Nuclear generating plant, the nation's largest nuclear power plant. (credit: Jeff Topping / Getty)

Each spring, nearly 1,000 highly specialized technicians from around the US descend on the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station near Phoenix, Arizona, to refuel one of the plant’s three nuclear reactors. As America’s largest power plant—nuclear or otherwise—Palo Verde provides around-the-clock power to 4 million people in the Southwest. Even under normal circumstances, refueling one of its reactors is a laborious, month-long process. But now that the US is in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, the plant operators have had to adapt their refueling plans.

Palo Verde is expected to begin refueling one of its reactors in early April—a spokesperson for Arizona Public Service, the utility that operates the plant, declined to give an exact start date—but the preparations began months in advance. The uranium fuel started arriving at the plant last autumn, delivered in the cargo bay of an unmarked semi truck. The fuel arrives ready for the reactor as 1,000-pound rectangular bundles of uranium rods that are 12 feet tall and about 6 inches on each side.

The latest shipment of fuel arrived at the plant well before the coronavirus pandemicbrought the world to a standstill, says Greg Cameron, the nuclear communications director at Palo Verde. The biggest change with this refueling cycle, he says, is the scope of the operation. “We’ve tried to trim down the amount of work to just what is necessary to ensure that we run for the next 18 months without impacting the reliability of the plant,” Cameron says.

Each of Palo Verde’s three nuclear reactors are ensconced in their own bulbous concrete sarcophagus and operate almost entirely independent of one another. This allows plant operators to periodically take one of the reactors offline for refueling and maintenance without totally disrupting the flow of energy to the grid. Each reactor is partially refueled every year and a half, with about one-third of the fuel in the reactor core being swapped out for a fresh batch.

No comments:

Post a Comment