I’ll admit it: When it comes to food, I’m lazy.

There are dozens of great dining options within a few blocks of my home, yet I still end up ordering food through delivery apps four or five times per week. With the growing coronavirus pandemic closing restaurants and consumers self-isolating, it is likely we will see a spike in food delivery much like the 20% jump China reported during the peak of its crisis.

With the food delivery sector rocketing toward a projected $365 billion by the end of the decade, I’m clearly not the only one turning to delivery apps even before the pandemic hit. Thanks to technology (and VC funding) we can get a ride, laundry service, car wash and even booze or marijuana delivered to our home or office at the push of a button. And the implicit trade-off we all make as consumers is that we are willing to pay a little extra for the convenience of having things delivered to our doorstep.

But while consumers have signed on to pay a premium for convenience, the food delivery ecosystem suffers from a lack of differentiation, compounded by an opaque and confusing web of markups and fees. In their quest to achieve profitability, today’s leading food delivery apps have thus far focused their innovation around new ways to charge consumers for the same items instead of innovating on differentiated products or services. Aside from a handful of exclusive delivery partnerships with a few premium restaurants, consumers are instead faced with a delivery market where the services are virtually indistinguishable, yet the price they pay for exact same item from the exact same restaurant can vary by 20% or more depending on the app they use.

Over the past decade we have seen a new wave of industry-leading technology companies emerge by focusing on innovation in otherwise commoditized markets, from financial services to consumer products. Buying stocks? Ordering a razor? Getting a prescription filled? From Robinhood to Dollar Shave Club to PillPack and beyond, today’s leading consumer companies have won through innovation and pricing transparency.

Competition between delivery companies with billions in funding is fierce, and with so much of that capital going toward chasing top-line growth through promos, discounts and other give-aways, innovation on core product has fallen by the wayside. In spite of the billions already invested into the food delivery sector by venture capitalists and massive growth projected in the years ahead, we believe that the industry is still in its infancy, and remains ripe for innovation. The ultimate winners will be those companies that achieve profitability and market leadership through the delivery of not just food, but better products, better services and transparent pricing.

Food delivery: The pricing matrix

To understand how the food delivery ecosystem prices the same items from the same restaurants so differently, we decided to do some research to see if we could shed some light on what you’re really paying for when you open that delivery app.

Before diving into the data, first let’s set the stage. The biggest names in food delivery apps in the U.S. are DoorDash, Uber Eats, Postmates and Grubhub (which owns Seamless). For the purposes of this analysis, we also decided to add Caviar to the mix — a more “premium” option available in larger markets that was sold to Square in 2014 and is now owned by DoorDash.

Next, let’s break down how pricing works. The core components of pricing across all food delivery apps are:

- Menu item: the actual food you are ordering

- Service fee: a fee charged by the delivery company for providing the service

- Taxes: sales tax on your order based on applicable local tax laws

- Delivery fee: the price for having the food delivered

- Gratuity: this is the optional tip for the delivery driver*

*Because gratuity is optional and not tied to any specific delivery service, we excluded it from the data set.

Process

Next, over several days in December we randomly selected 10 restaurants each in Los Angeles, New York and San Francisco that were available on at least four of the five apps and selected the same menu item for delivery to the exact same address. We compiled all data over a 48-hour span and tried to compare pricing for each restaurant/food item combo as close to the same time of day as possible. We then broke down all pricing by the individual components and put the line-item data into a spreadsheet for comparison (link to raw data set shared at the bottom).

Finally, to help clarify the differences in pricing, we introduced a new metric called Total Meal Cost (TMC) to refer to the overall amount it costs to order a meal through a delivery app, compared with ordering that same meal directly from the restaurant. We will refer to the cost when ordering directly from a restaurant as the Restaurant List Price (RLP).

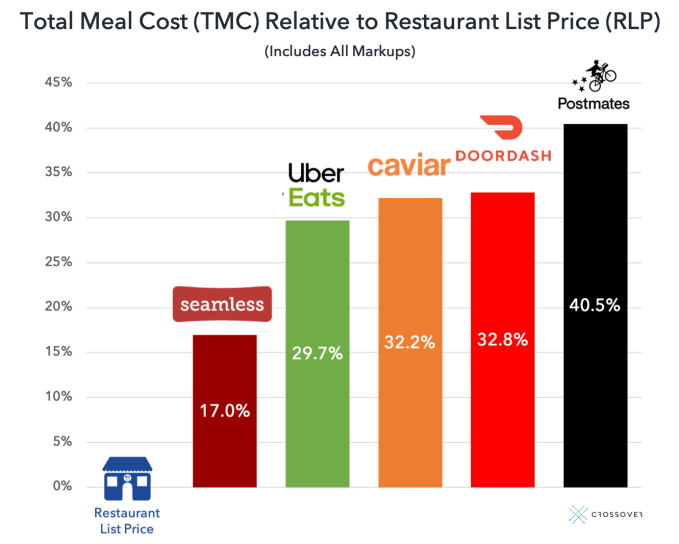

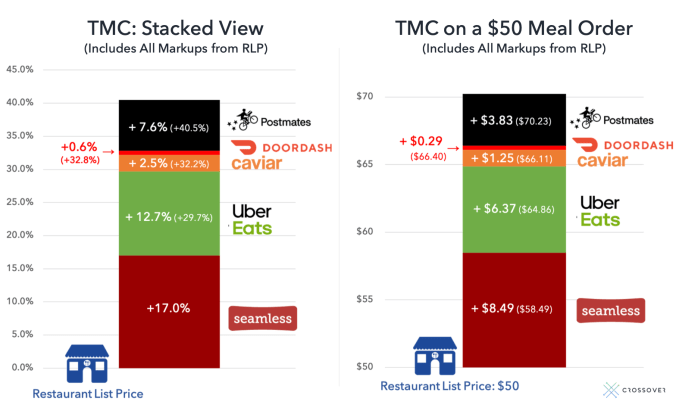

So without further ado, here’s what we learned: While as consumers we expect to pay a premium for the convenience of the service, it turns out there can be a very significant difference between both the price you would pay when ordering directly from a restaurant, as well as what each of the delivery apps charge for the exact same item. When accounting for TMC, on the low end of the spectrum you’d pay an extra 17% over RLP when ordering via Seamless, while on the high end you would shell out a whopping 40.5% more when using Postmates.

To put the markups in further context, if you ordered $50 worth of food from a restaurant, the TMC would come to $58.49 through Seamless compared with $70.23 if you order through Postmates. The graphic below demonstrates how all the apps stack up.

In addition to looking at the overall TMC, we also wanted to zoom in on the data so we could better understand how each of its components — service fees, delivery and even taxes — compare. From a pricing perspective, it seems natural that delivery fees would have the most variability. We’ve all been trained by Uber and Lyft to understand supply and demand and that during busy times delivery can be more expensive (aka everyone’s favorite, “surge pricing”). So while money is money and delivery cost certainly matters, we wanted to also look at how the markup of each component of the TMC differs across the various apps. You can see the summary data below.

One of the biggest take-aways is that Seamless’ comparative price advantage is largely driven by its low service fees. In fact, in 21 of the 28 data points available for Seamless, the company charged no service fee at all. Uber Eats’ comparative advantage is driven primarily by its low delivery fees — likely the result of having an established fleet of drivers and logistics expertise derived from the company’s core ride-hailing business. This offsets their highest comparative markup of menu-item list price. Postmates gets the triple-whammy of high markup, high service fee and high delivery fee. Caviar generally huddles in the middle of the pack on all variables, though its service fee is pretty hefty for Los Angeles residents, at 18%. DoorDash falls victim to its delivery fees, which as the highest in the batch undermine their comparatively low menu markups and service fees.

Other observations

In addition to the high-level take-aways, a few other things we found interesting in the data:

- Meal price markups over RLP in the delivery apps vary by city. On average across all five delivery apps, Los Angeles was marked up the most (6.49%), followed by San Francisco (5.98%), then New York (1.77%)

- Service fees:

- Different Approaches. Uber Eats and DoorDash are consistent in their service fee pricing being pegged to 15% and 11%, respectively. Seamless does not typically charge a service fee. Caviar and Postmates are less clear and consistent on their service fees, though Caviar has a cap of 18%.

- Service fee fluctuation by market. Service fees hold steady across the three surveyed markets for Uber Eats, DoorDash and Seamless, while fluctuating up to 3% across Postmates and Caviar.

- Delivery fee fluctuation by market. On average across the five delivery apps, San Francisco has the most expensive delivery fees ($2.58), followed by New York ($2.08), then Los Angeles ($1.88).

- Other Fees:

- Postmates “Merchant Fees.” In three of the 29 restaurants surveyed that Postmates serves, the company tucked a $1.00 “Merchant Fee” into the Service Fee section, where other delivery apps did not.

- Other Fees. Depending on the market, some restaurants charge a small “bag fee,” which most apps typically fold into the service fee. This is mostly why Uber Eats and DoorDash service fees aren’t exactly 15% and 11%, respectively. Additionally, several charge “minimum” order fees.

- Market share: We didn’t dive specifically into the number of restaurant options available per service per market — that would warrant an entire study in its own right. But other publications have done solid research comparing relative market share, and for the purposes of this analysis, each of the delivery services offered no shortage of options across cuisines.

A quick note on taxes

Taxes charged by the five delivery apps actually showed some variance, as well, and there is significant legal debate currently around how taxes should be calculated. That’s a whole separate article in itself, so we will leave that to the legal experts, as tax rate fluctuation across the apps was 1.1% or less. But it’s still fascinating that with billions of dollars of transactions flowing through these apps, the tax question still remains unanswered.

It’s not just the delivery apps

It’s worth noting that the TMC markup over RLP that consumers experience isn’t entirely at the hands of the delivery services. We spoke with several restaurants about their delivery partnerships and best practices, and several noted that even though delivery partners strongly discourage doing so, they often elect to increase on-app list prices when selling through delivery apps as a way of offsetting the up to 30% fee the delivery apps charge. And while we have not seen any egregious examples of menu pricing markups, in talking with several restaurant owners we were surprised to learn that the delivery companies themselves often list restaurants they have no formal relationship with. The restaurants don’t have to pay them a fee, but as one restaurant owner told us, “Yes, theoretically any non-partner app could list one of our salads for $4,000” and any added profit would go entirely to the delivery service, much like a concert ticket scalper earns profit that doesn’t go back to the artist or event producer.

“Differentiation” today

The Exclusivity Land Grab

As noted above, the primary differentiation between delivery apps today is not based on innovations that meaningfully impact user experience, but instead comes down to a handful of restaurant brands with which the various apps are in a land grab to create exclusive delivery relationships. For example, Postmates has the trendy Sugarfish sushi in Los Angeles, Uber Eats had McDonald’s (until the chain recently added DoorDash), Caviar has local San Francisco favorite Souvla and DoorDash has Outback Steakhouse. While this strategy may help for those users that order religiously from these restaurants, reports suggest that the national chain deals are coming at a major cost to the delivery companies.

Memberships

The other “innovation” focus for some of the delivery services today is a focus on pushing users toward their respective loyalty plans as a way of locking in more predictable revenue and creating brand loyalty in an otherwise commoditized offering. These plans generally include a monthly fee in exchange for no delivery fee for orders above a certain minimum, and include Postmates Unlimited ($9.99/month or $99/year), DashPass from DoorDash ($9.99/month + tie-in for Caviar) and Uber offers a rewards program that works across Eats, rides, bikes and scooters.

Opportunity to innovate

Getting millions of meals delivered quickly, accurately and still warm (or cold) from restaurants to consumers each day is no easy feat. Continually improving the core logistics associated with this undertaking requires massive funding and ongoing investment. You can only play phone tag with your delivery driver and receive a soggy Egg McMuffin so many times before you give up on paying a premium for the convenience. That said, delivery apps must equally invest in consumer-facing innovations if they want to build sustainable brands and reach profitability.

There are far better product minds who can opine on the best ways to innovate on the delivery app experience, but a few examples of features we came up with after consulting fellow delivery addicts include:

- Personalization: Instead of today’s rudimentary search functions, apps that learn “he is lactose intolerant” or “she hates tomatoes” and use AI to improve both search and meal recommendations.

- Multi-location ordering (e.g. sushi and pizza in the same order), which will be further enabled through the growth of multi-tenant virtual kitchens (see below).

- Revamped packaging: Keep hot items hot and cold items cold while exploring more eco-friendly options that save money and the environment.

- One-tap order button for your most-frequently ordered meals.

- Customization: The ability to better support options beyond the confines of a fixed menu — the infrastructure to support “create your own” at scale and provide data back to restaurants to influence ongoing menu development.

- Pictures and reviews: Delivery apps should be able to better leverage their millions of users to collect more data from customers than restaurant-level reviews. The apps that better harness item-level reviews, imagery and similar data will make it harder for others to keep up.

- Premium offerings: Similar to choosing Uber Black, users can pay extra for premium service, such as rush orders that skip the line or setting the expectation that the delivery driver brings items to your front door (versus curbside).

- Diet and nutrition: Better nutritional data and search functionality (such as searching by calories or Keto), as well as integration with health and fitness-tracking apps and popular diet plans.

- Social feed: This may be a stretch, but a social feed of orders among your personal network, similar to Venmo or Snackpass — with integrated gifting.

- Rewards: Other than Uber’s platform-wide rewards program, apps have yet to effectively tap into the power of loyalty and rewards, both at the app level and as a service to be offered at the restaurant level.

Conclusion

So what does it all mean? Well, it’s no secret that companies in the on-demand economy are still struggling to figure out how to make the economics work as both public and private investors become increasingly impatient. In the meantime, the push for profitability has also resulted in questionable labor practices, such as DoorDash applying tips toward its delivery workers’ wages, effectively asking customers to subsidize the wages so the company didn’t have to pay their workers their guaranteed delivery minimum out of pocket (a practice the company has since reversed after public outcry).

As the on-demand food delivery economy continues to hurtle toward a projected $385 billion by 2030, it has also begun to reshape the global restaurant industry. As more and more consumers opt (or are ordered) to stay home and press a button for food instead of going out, restaurant owners are increasingly choosing to forgo expensive real estate and front-of-house staff, and are instead expanding into virtual kitchens that cater exclusively to the on-demand audience. This transition from traditional to “virtual” restaurants may prove to be one of the defining platform shifts of our time, and the venture community has taken note. As the virtual kitchen market grows, so too will the demand for the apps that get the food from the delivery-only commercial kitchens to consumers.

As the battle for market share and profitability heats up in the new wild west of food, consumers have demonstrated they are willing to accept the implicit trade-off of paying a premium for convenience. But as this industry pushes forward toward profitability and sustainable operations, we believe that the companies that embrace transparency and innovate on the core product and service — not on pricing markups and services fees — will emerge as the winners in the new food economy.

Now, what should I order for dinner tonight… and better yet, which app do I use?

Notes

- With only 30 data points per company, a single outlier can skew the data. That said, we believe the data set is sufficient to support our core takeaways.

- The same address was used for all orders in each city.

- All data was pulled in a 48 hour weekday period and at approximately the same time of day.

- Some apps offer a form of membership plan where delivery fees are waived in exchange for a paid membership fee. All data here excludes any special membership programs.

- Promos, specials, or any other discounts were excluded from the data set — if a promo was auto-applied, the original price was used.

- No “surge” pricing was used in any of the delivery fee data.

- All of the apps have “preferred” relationships with a subset of restaurants. This was not factored into the data set.

- The full data set can be accessed here.

Thanks to Josh Elman, Blake Ross, Jesse Lichtenstein, Jared Morgenstern, Roylene Kralich, Nicolas Bernadi and Sam Kokin for their help on this post.

No comments:

Post a Comment