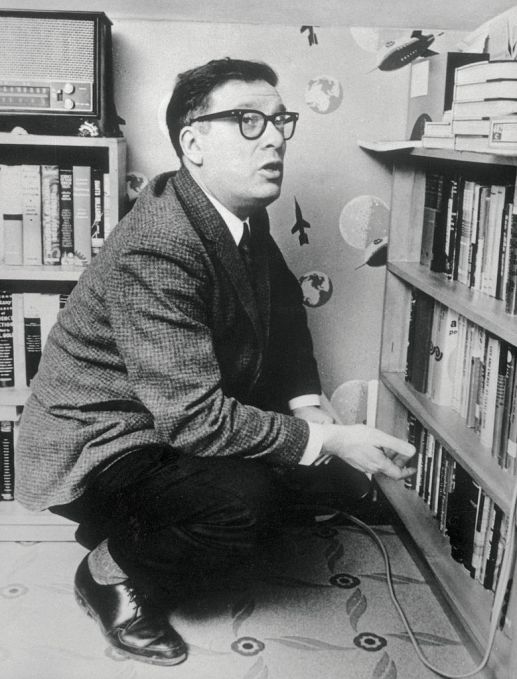

In his recently published book “Astounding,” the author Alec Nevala-Lee brings American science fiction’s Golden Age back into focus by following four key figures: John W. Campbell, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard — and Isaac Asimov, who officially turned 100 today (his exact birth date was unknown).

Nevala-Lee’s warts-and-all portrait paints Asimov — known to his fans as the Good Doctor — far more sympathetically than the genre’s other founding fathers. He’s charming and self-deprecating, generous to other writers and editors, a politically progressive thinker and a tireless defender of science and rationality.

But Nevala-Lee is clear about another aspect of Asimov’s story: He was someone who unapologetically groped women.

As recounted in “Astounding,” Judith Merrill said Asimov was known in his younger days as “the man with a hundred hands.” Harlan Ellison wrote, “Whenever we walked up the stairs with a young woman, I made sure to walk behind her so Isaac wouldn’t grab her tush.” And Frederik Pohl even recalled Asimov telling him, “It’s like the old saying. You get slapped a lot, but you get laid a lot too.”

And these aren’t the words of Asimov’s critics or detractors; they’re his friends and peers. Asimov’s habits were so well-known that in 1962, the chairman of the World Science Fiction Convention invited him to give a talk on “The Positive Power of Posterior Pinching.”

I’d already heard rumors about Asimov’s behavior back in 2014, when I wrote a birthday essay for BuzzFeed describing him as my favorite author. But I limited the piece to my personal relationship with his work — to the ways in which the Foundation and Robot books turned me into a lifelong science fiction fan, and how his wide-ranging nonfiction expanded my horizons.

Six years later, Asimov remains one of my favorites (alongside Ursula Le Guin, Samuel Delany and Philip K. Dick). And I’ve been happy to sing his praises when he’s in the news.

Still, it seems increasingly difficult to ignore the less admirable aspects of his personality. Fans, friends and other defenders might argue (as Ellison did) that “times were different,” that Asimov saw his behavior as “harmless” and that it’s a relatively minor blemish on his otherwise laudable career. But harassment at conventions is a serious problem, and if Asimov hadn’t died in 1992, it’s hard to imagine that he would have (or should have) escaped the #MeToo era unscathed.

Television critic Emily Nussbaum confronts some of these issues in her essay “Confessions of a Human Shield,” in which she asks, “What should we do with the art of terrible men?”

In the past, Nussbaum says she followed the conventional method of separating the art and the artist: “Decent people sometimes create bad art. Amoral people can and have created transcendent works. A cruel and selfish person — a criminal, even — might make something that was generous, life-giving, and humane.” But now, she admits that “the sociopath’s approach” no longer satisfies.

That’s particularly true with Asimov, whose personality seems inseparable from his work. One of his strengths as a writer was his ability to be clear, conversational and personal. When you read one of his science books or essays, you come away feeling like your good friend Isaac has been explaining things to you in a way that you can finally understand. Even his science fiction is usually prefaced by autobiographical essays written in that same friendly voice.

So for me, it’s not simply a question of separating the art and the artist. It’s about acknowledging that so much of what’s admirable in Asimov’s writing seems to emanate from the man himself — and that, like or it not, he did more to shape my worldview than any other single writer, convincing me (as I put it six years ago) that “ideas matter and the universe can be explained” — while also acknowledging how indefensibly he treated women.

And in the end, it may be something simpler that poses the biggest threat to Asimov’s reputation — namely, the passage of time.

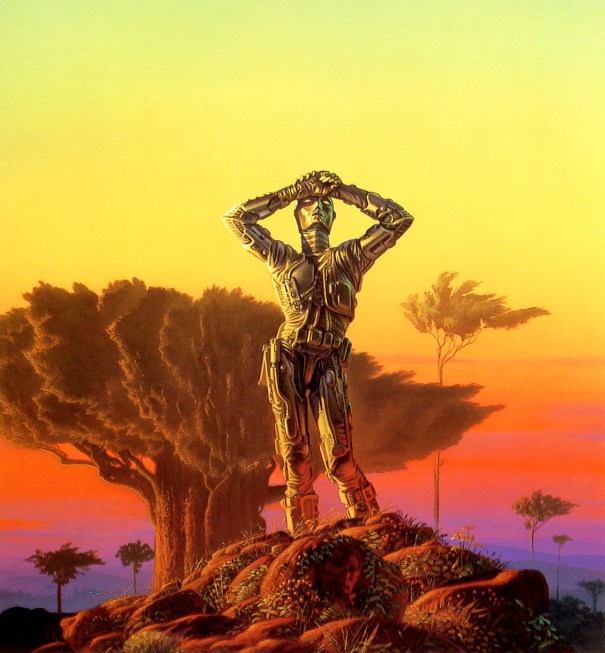

Science fiction has changed dramatically in the past decade, with a gratifyingly diverse group of writers reshaping the field. A new canon is forming, one that doesn’t center on Asimov, Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke. As the writer John Scalzi put it, “Heinlein and Clarke and Asimov and etc were and are titans. But remember that the titans were overthrown by newer gods — and that those gods themselves were supplanted over time.”

Getty Images

This is probably how it should be. After all, Asimov’s work is very much of its era. Readers in 2020 and beyond will have an increasingly difficult time recognizing the future he depicted: a future without personal computers or the internet, and in which no one finds it remarkable that every single scientist, politician and person of importance is a man. (The major exception being the roboticist Susan Calvin, who’s still defined by her preeminence in a male-dominated field.)

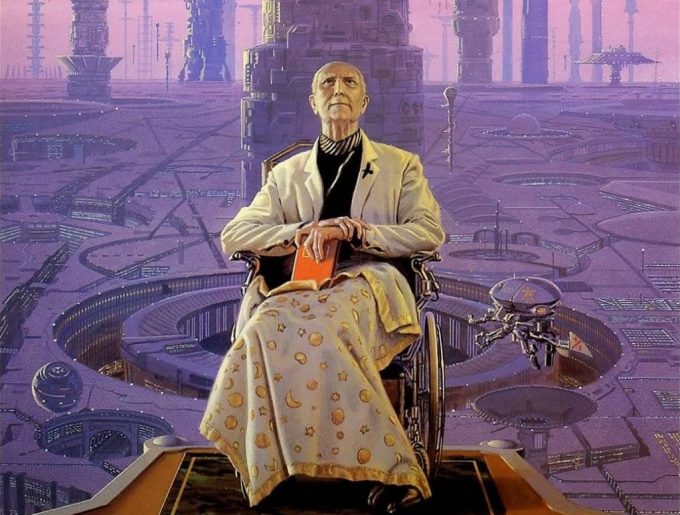

Not that I think Asimov is about to fade into obscurity. In fact, Apple is producing a new TV+ series based on his Foundation stories, which take place over hundreds of years, depicting the efforts of a small group of scientists to rebuild civilization after the fall of the Galactic Empire.

So Asimov will probably be reentering the conversation soon. And despite my reservations, I’m glad.

Because for all the ways in which he might have missed major technological trends, and for all the ways in which his worldview was rooted in the 1930s and ’40s, Asimov still speaks to the challenges we face today. Not just in his famous Foundation and Robot stories, not just in the essays in which he defends science against religious fundamentalism, but also in “The Gods Themselves,” which I recently reread. Published back in 1972, the novel remains scarily prescient in its depiction of how humanity’s stupidity, greed and attachment to cheap energy can blind us to an existential threat.

And one of Asimov’s major subjects was the very passage of time that’s eroded his prominence in the field. His best work makes that it clear each generation will be eager to leave the last one behind, that it must face new problems with new ideas.

Despite his very real flaws as a writer and as a person, he encouraged us to search for those better ideas and work for that better future. That’s why his books will always have a place on my shelves. And that’s why I hope he’d be happy to give up some of that shelf space to writers who don’t look, think or write like him.

No comments:

Post a Comment