A couple of years ago, the cofounder and CEO of the blood-testing company was publicly taken to task for implying in articles and professional profiles that he has a PhD when in reality, he’d left a prestigious graduate group three years after enrolling, without a degree.

The CEO is hardly alone in intentionally or otherwise sewing confusion around his credentials, however. Over the years, we’ve mistakenly believed that a number of founders have obtained specific college degrees based on their LinkedIn bio, only to learn offline that they enrolled for some period of time in a particular program that they didn’t complete.

It happened most recently with the cofounder of a startup who one would might surmise based on his LinkedIn profile has a master’s degree from Harvard but does not. We also misunderstood the CEO of a robotics company to have a PhD based on her LinkedIn. It was our fault; it mentioned under the credit that she’d left to start a company. But anyone scanning the site might have come to the same wrong conclusion. (We pointed this out to her team, and mention of the PhD program on her LinkedIn page was deleted.)

In a high-profile case, James Damore, the fired Google engineer who authored that infamous memo about the company’s diversity practices and whose LinkedIn page cited under “Education” a “PhD, Systems Biology,” removed mention of those doctoral studies after Wired confirmed with Harvard that he was enrolled in the program but didn’t complete the doctorate.

Damore tried to defend his own LinkedIn profile, tweeting at the time, “I never told anyone I have a PhD. LinkedIn can’t distinguish between being in the PhD program and having a PhD (I forgot to update it).”

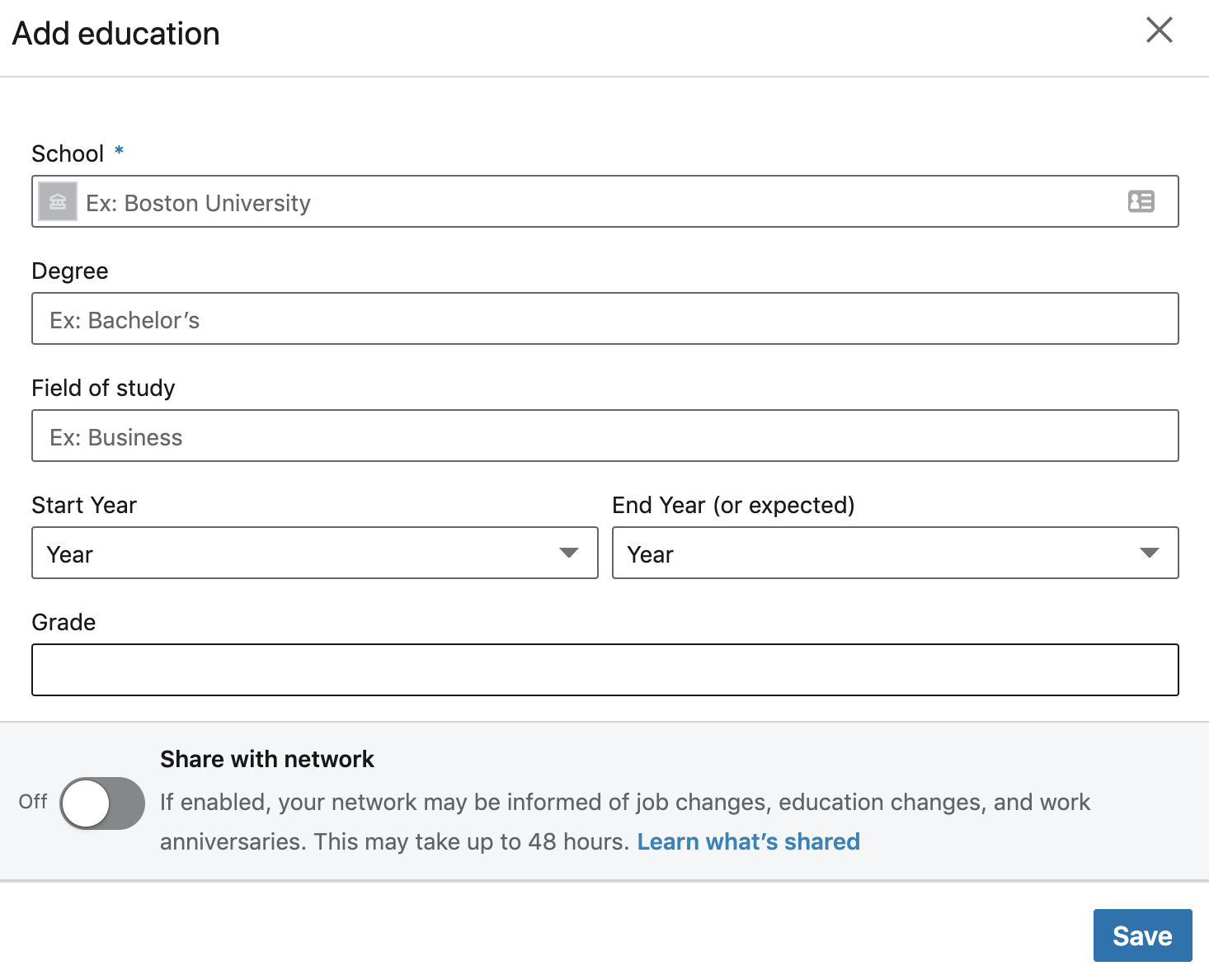

Though few on Twitter found him credible, he wasn’t mistaken on this front. In creating a profile on LinkedIn, the choices one is given are to a.) list a completed degree and leave off anything partially completed, no matter how much time was invested in a program (or minuscule its acceptance rate) or b.) list an incomplete degree without a clear way of explaining that it’s no longer being pursued or whether it will ever be obtained.

LinkedIn doesn’t view the issue as its fault. Asked whether LinkedIn members might be posting incomplete degrees because of the company’s user interface, a spokesperson emailed us today, writing that LinkedIn’s user agreement and “professional community policy” guidelines — which, of course, no one reads or cares about — are “clear that members should provide factual information about themselves on LinkedIn.”

Added this person: “People should definitely add their education details to their LinkedIn profile. The education section includes ‘Start Year’ and ‘End Year (or expected)’ fields. If a member has a partial degree, we recommend they clearly state the status of their degree within the ‘Degree’ and/or ‘Description’ fields.”

Still, that “description” field isn’t easy to find, and why LinkedIn — which has more than 600 million users — hasn’t added fields for partially completed degrees is a bit of a mystery.

Cynically we will note that LinkedIn makes a lot of its revenue off recruitment services. Before it was acquired by Microsoft, and the companies’ financials were consolidated, 65 percent of LinkedIn’s revenue came from recruitment services. And often the more distinguished the degree, the more people will pay to associate themselves with the ostensible degree holder. (LinkedIn itself strongly encourages loading up one’s profile with education-related details, saying these attract “11x” more profile views.)

A much bigger factor, however, is human nature, argues Stanford professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, a renowned professor at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business who has written extensively about organization theory. Asked if he has reason to think that more students are listing incomplete degrees on LinkedIn — or even dropping out of school with less compunction, knowing they might — he points us to numbers published in 2001 by the payroll and benefits managing company ADP.

What they show: of 2.6 million background checks that the company performed that year, 44 percent of applicants were discovered to have lied about their work histories, 41 percent lied about their education, and 23 percent falsified credentials or licenses.

“People lie about everything all the time,” says Pfeffer. “I’m not sure that it’s any worse now than it was 10 or 20 or 30 years ago.”

It’s something recruiters anticipate, he says. He recalls a conversation with a top executive from the search giant Heidrick & Struggles, who Pfeffer had interviewed for one of the many books he has authored. “He said to me, ‘So many people make up credentials that we no longer use fudged credentials as a reason to disqualify a candidate.’ He said recruiters will correct what they find wrong with someone’s resume. But he said if they used exaggerated — even made-up — credentials as a reason to disqualify people, they would never have enough candidates.”

LinkedIn’s limited menu of options may give more cover to people. But Pfeffer cautions not to assign the company too much blame, no matter its reach. It’s a little like shooting the messenger, he suggests.

“Sure, LinkedIn could play some role. But they could change the way they operate tomorrow, and people would still find a way to make themselves look more accomplished than they are.”

No comments:

Post a Comment