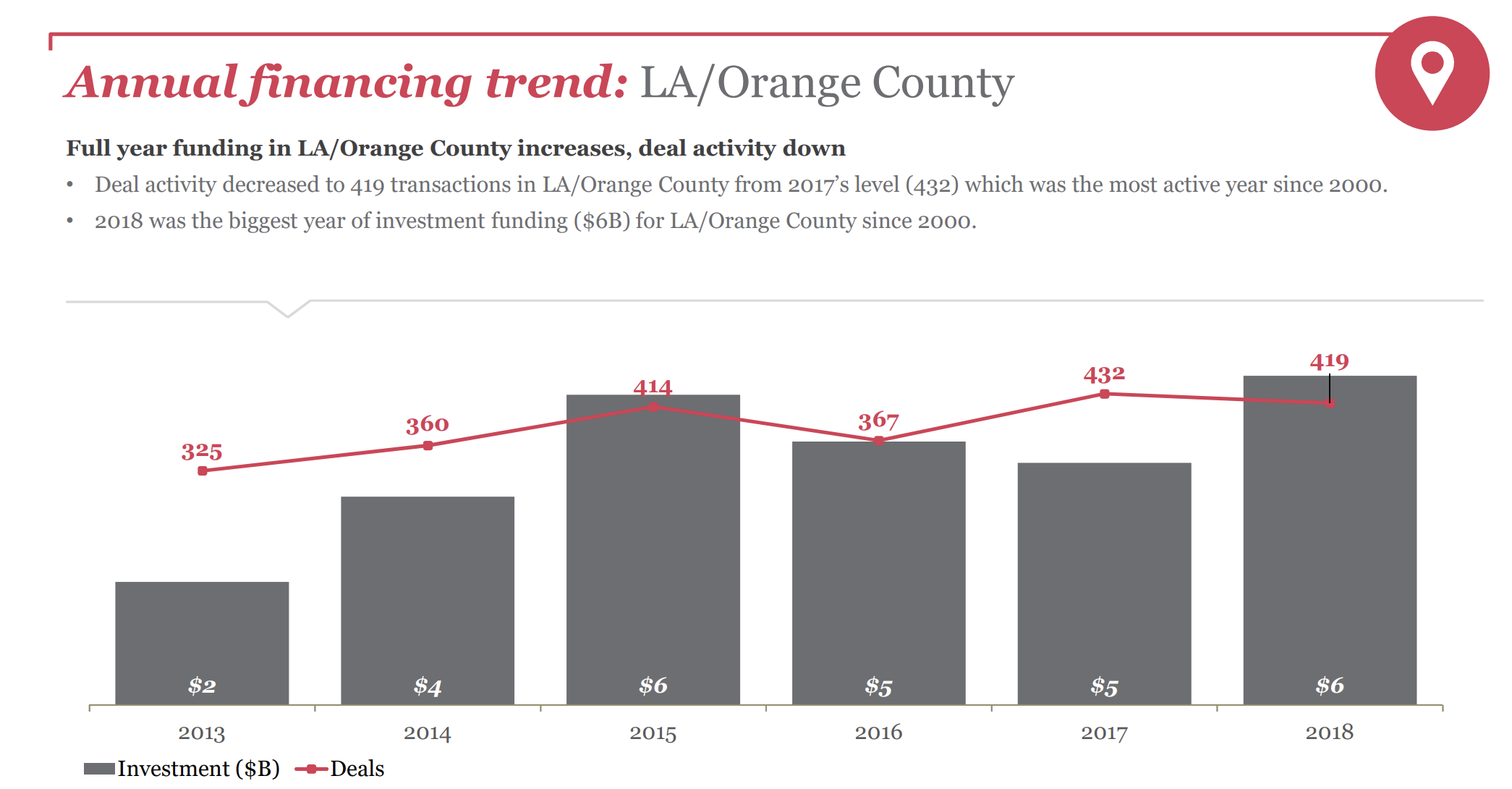

The Los Angeles startup scene has come a long way in the three-and-a-half years since Marlon Nichols, Troy Carter and Trevor Thomas launched Cross Culture Ventures. The city and its surrounding Orange County exurbs were at the beginning of a venture capital surge that has seen invested capital in the region rise from $3.63 billion in 2015 to $6 billion last year.

Since Cross Culture landed on the Los Angeles scene with a $50 million fund, Nichols and his partners have notched three exits and seen the paper value of the fund’s portfolio grow by an aggregate of 2,085 percent, according to people with knowledge of the firm.

And Nichols and his partners have done it by backing one of the most diverse pools of startup founders in any firm’s portfolio.

The road to Cross Culture

The path from growing up in one of the towns on the outer edges of New York to the center of Los Angeles’s burgeoning venture capital industry wasn’t a straight line for Nichols (unlike many other venture investors). Cross Culture’s architect had to make his own way through the tech ranks after college, through a professional career in Europe, then back to business school before finally landing an opportunity with Intel Capital.

His father had worked as a train engineer in Jamaica and relocated the family to New York, where his mother worked as a housekeeper before getting her beautician license and opening her own shop. The couple had moved from Jamaica two years before Nichols would take the trip himself — time he spent living with his aunt and grandmother.

Marlon Nichols, co-founder and managing partner, Cross Culture Ventures

Growing up in Mt. Vernon, NY, just north of the Bronx where he’d moved with his parents, Nichols had always expressed an interest in technology. He’d been playing around with computers ever since his parents bought him a Commodore 64.

The first person to attend college in his family, Nichols transferred to Northeastern’s newly developed major in Management Information Systems after starting out in architecture. College gave Nichols his first exposure to life in Silicon Valley, as well. Northeastern had an internship program that sent students out of Boston to try their hands in the business world — and Nichols was placed at Hewlett Packard in Cupertino, Calif.

He’d intended to move out to Silicon Valley after graduation, but instead took a job in the Boston offices of Frictionless Commerce — and it was there that Nichols first confronted the constraints that the city’s lack of diversity could mean.

“In Boston there was definitely a racial undertone,” says Nichols. “Going out as a professional… you weren’t treated well.”

He took the opportunity to move to London when it was presented and spent a few years there — playing semi-professional basketball in the evenings and working for Frictionless Commerce during the day.

After the company’s acquisition by SAP in 2006, Nichols consulted at the Blackstone Group and Warner Media. “In those rooms I was again the only one [who was a minority],” he says. “I started getting annoyed by it and started thinking about it a little bit more — I thought about education and opportunities and just knowing that there’s even an opportunity out there for this career path.”

So Nichols created a nonprofit that would help inner city students get into colleges. “I never had an SAT prep-course,” says Nichols. “I didn’t have anyone coaching me.”

The program helped students start to think about applying to Cornell, Vassar and Penn, when they were initially thinking about City University in New York.

As the nonprofit took off, Nichols returned to school — Cornell University on a full scholarship to its business school.

“When I started going through that process I saw even fewer of the folks that looked like me,” Nichols recalls.

From Cornell, where Nichols ran the university’s venture capital fund, he was recruited to Intel Corp. as part of a management training program. Although Nichols was supposed to rotate through three different business divisions at Intel, once he was placed in Intel Capital he advocated to stay there.

And it was there that he was able to bring his passion for creating opportunities for under-represented minorities and women to an industry that sorely needed it.

It was around the time that the diversity numbers at big technology companies — long held as an island of meritocracy in a sea of industries that were rife with sexism, racism and nepotism — were generating more criticism. When Tracy Chou called for reporting on diversity numbers in 2013, Nichols saw a repeating pattern that perhaps he could do something about at Intel.

Alongside Lisa Lambert, a managing director in Intel Capital’s software and services group, Nichols, who’d been in the new user experience group at Intel Capital, advocated for the creation of a diversity fund at Intel.

“We thought that there’s got to be a way that the folks in charge of deploying capital can be involved in diversity,” Nichols says of the creation of the fund. “Diversity was front and center and then it goes away and then it’s front and center again… There had to be something that could be done from a venture perspective.”

While the diversity fund had no problem finding companies to invest in, these companies were having trouble when they sought additional capital in subsequent rounds, said Nichols.

“I saw that some of the companies — after receiving the funding — were having trouble being viewed as a high-class company which had raised money from one of the largest institutional investors in the world,” says Nichols.

The problem, as Nichols sees it, is that these companies were solving global problems for a broad base of consumers, but their perceived financing as a “diversity” play was an obstacle to their future success.

“I was like, all right… I’m not going to put this tag on their back that would make it difficult for them to raise capital in the future,” Nichols says. “Instead I’m going to look at culture from a global perspective and try to identify emerging trends — if we are successful in doing that — and can be successful in picking trends — I’m going to get a high number of diverse entrepreneurs solving problems for the 99 percent.”

Chart courtesy of PWC Moneytree/CB Insights

Cross Culture and the Los Angeles opportunity

By the time Nichols was ready to form Cross Culture, other obstacles had emerged at the Intel fund. The focus on diversity had predominantly settled on trying to address venture’s gender problem to the exclusion of other representation issues that Nichols thought the firm had to deal with: race and ethnicity.

In addition, many of the entrepreneurs solving problems in billion-dollar industries that Nichols identified didn’t fall within the Intel mandate. The corporate investor had to back companies that aligned with its strategic vision — something of a challenge when advocating for investments in consumer-focused beauty products for the African American community (for instance).

So, after a stint in the Kauffman Fellows program, Nichols came away with a desire to strike out on his own with the help of a few anchor investors (like Freada Kapor Klein). Klein introduced Nichols to Troy Carter of Atom Factory as another potential investor in the fund.

“I flew down to L.A. and I sat with Troy… we talked for two hours and we really got along and… at the end of the meeting he said, ‘Good to meet you, but I’m not going to invest in your fund.’ ”

Two weeks after that initial rejection, Nichols got another call from Carter — instead of investing, the music impresario suggested a partnership. With Carter on board as founding partner, the two began laying the groundwork for the fund that would close on its first capital within the next year.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – SEPTEMBER 23: Troy Carter of Atom Factory speaks onstage during TechCrunch Disrupt SF 2015 at Pier 70 on September 23, 2015 in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Steve Jennings/Getty Images for TechCrunch)

Cross Culture has built a portfolio where 72 percent of the founders are white women and women and men of color. It’s the only firm to back several African American founders that have gone on to raise significant capital in their A or B rounds, including Blavity, PlayVS, Mayvenn and WonderSchool.

The firm has also already enjoyed some success from early exits.

Gimlet, the podcasting company that Cross Culture backed at a $36 million post-money valuation, sold to Spotify for approximately $230 million. The firm’s other exits include MessageYes, which was sold to Nordstrom, and Skurt, which was acquired by Fair in February of last year.

Nichols has been instrumental in getting the firm in front of fast-growing companies like Airspace Technologies, a provider of on-demand logistics services; PlayVS, the company bringing esports to high schools around the country; and the new mobility company revolutionizing rental cars, Fair. These companies have all seen their value jump in recent months.

After Cross Culture was given the opportunity to invest in Fair through the Skurt acquisition, Fair’s valuation increased by 150 percent when SoftBank added another $385 million in financing to the rental car company. Airspace’s valuation saw a 733 percent increase in less than eight months when Scale Venture Partners led the company’s $20 million Series B (at a valuation over $100 million) and PlayVS saw its value increase by 329 percent in the six months since Cross Culture invested, according to a person familiar with the fund’s portfolio.

Diishan Imira, the chief executive of Mayvenn, recently raised $23 million for his business selling hair extensions and beauty products to the African American community, up from the $10 million the company had closed when Cross Culture invested as part of the startup’s Series A.

Mayvenn was Cross Culture’s first investment and is a testament to the long-term relationship building behind much of Nichols’ work in the venture community.

“Kirk Collins put together a group of four or five people to get together for me to pitch to and for me to get some money. Marlon was one of the people there… and me and Marlon argued the entire time,” Imira says of that first meeting with Nichols. “We argued for 30 minutes and nothing came of it. But we kept in touch. He always offered advice or support here and there. He kept tracking us. And then… prior to our whole Series A… he had just started Cross Culture. I was like ‘Yo man, I want you guys to come in.’ ”

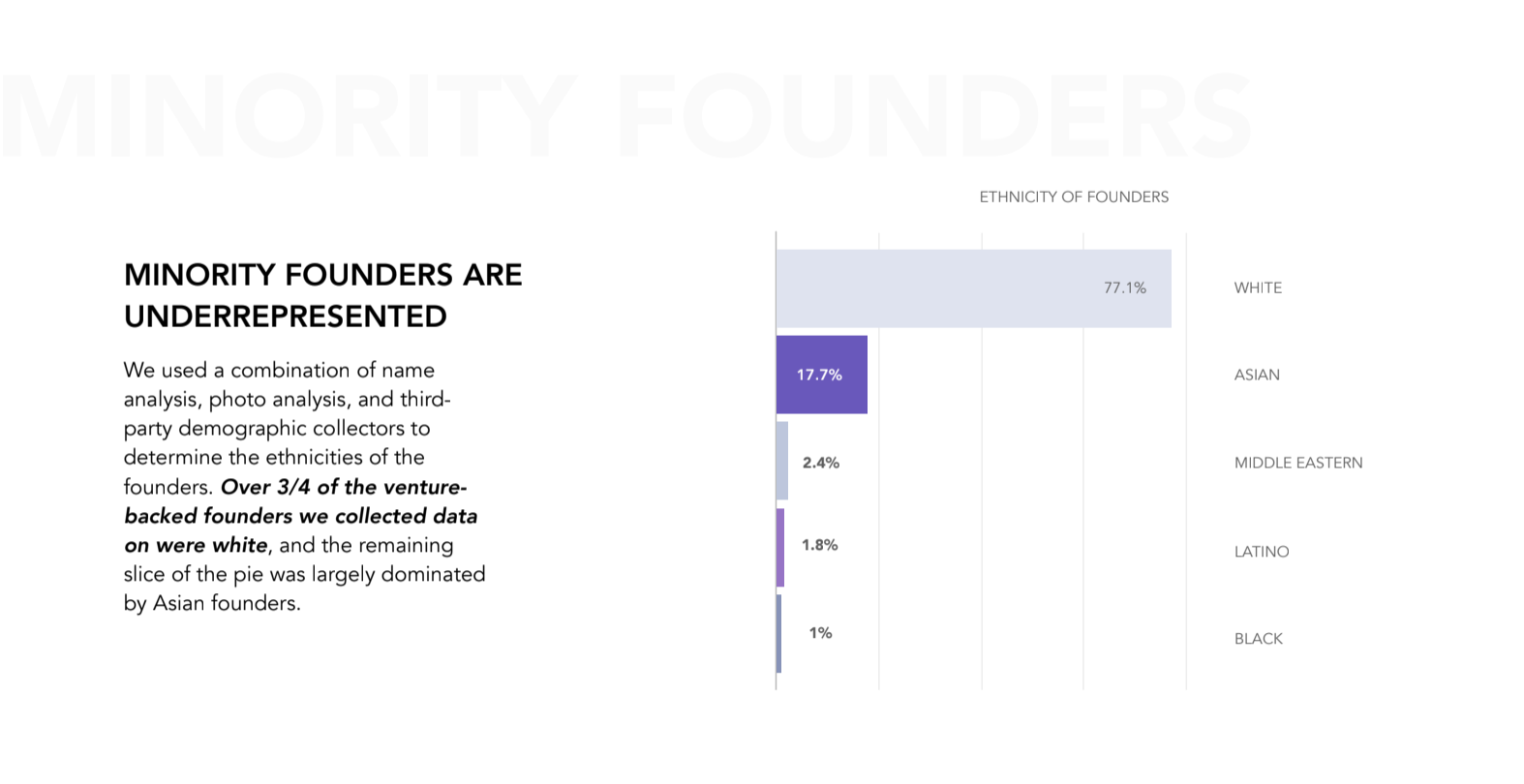

Meanwhile, the problem of representation in venture capital was not improving, as the rest of the venture capital industry is failing to keep pace. Only 1 percent of founders of startup companies receiving venture capital backing are African American, and only 1.8 percent of founders are Latinx, according to data from RateMyInvestor and Diversity VC.

Nichols sees a potential to reverse those trends by focusing on cities and investing in ecosystems that have been historically ignored by venture capital’s white-shoe firms and traditional rainmakers.

“We had an office in Palo Alto and an office down here in Culver City,” Nichols recalled. “For the first two years I would come down every other week and Troy would come up every other week. [But] coming down here I could see there was something happening that I hadn’t seen before. Unlike in the Bay Area, I was seeing things being created for a greater percentage of the population.”

Fueled by exits in Dollar Shave Club, Snap and Oculus, more capital was coming in to the ecosystem to back a more diverse group of founders who’d proven they could find success south of the Bay Area.

“Most of the things that are coming out of the Valley these days are meant to be used by people in the Valley as opposed to people in the Bronx, or Queens or Baltimore,” says Nichols. “This is the time to be here. If you are going to invest in the companies of tomorrow you have to go where the world is moving to — and that’s black and brown, honestly.”

The census supports Nichols’ assessment. By 2044, the United States will see a majority minority population, and the next generation of consumers is already showing its preferences. Companies like Ipsy, founded by Michelle Phan, is a billion-dollar beauty business built by a minority founder; Pat McGrath Labs, another billion-dollar makeup brand launched by make-up artist Pat McGrath, raised $60 million from Eurazeo Brands.

Cross Culture isn’t just sitting in Los Angeles waiting to find these companies. Nichols and his firm are taking the opportunity on the road. He spent a month in Miami meeting with entrepreneurs and has organized a series of “Culture and Code” events in Detroit and Atlanta to get exposure to startups in those cities as well. Nichols describes them as pop-ups to meet entrepreneurs and investors in those communities.

For Cross Culture, the decision to travel to these urban hubs far from technology’s traditional perch in Silicon Valley is simply an extension of the firm’s broader vision.

“Only 2 percent of venture capital is black and Latinx and .002 is black women. Part of that is that young folks that look like me don’t know what venture capital is,” says Nichols. “It was kind of eye-opening in the sense of how a good portion of our population thinks about these demographics and what they’re capable of and it was very sad.”

Now, as Cross Culture is mostly deployed, the firm needs to make a decision about its future. There’s the potential that Cross Culture could go out for another $50 million to $100 million, or, potentially raise a larger new vehicle.

To date, the firm’s average investment size has been roughly $250,000 into the 34 companies the firm has backed so far.

For Nichols, the success of these companies is an imperative. Not just to make money, or to prove out his thesis, but because of what failure would mean for other firms that take a broad approach to their investment thesis trying to back the best founders — no matter their background. Nichols believes it’s important for the venture industry, for the economy and for the broader society.

“There is no way I can fail at this,” Nichols says. “I have to win.”

No comments:

Post a Comment