Tech Nuggets with Technology: This Blog provides you the content regarding the latest technology which includes gadjets,softwares,laptops,mobiles etc

Sunday, November 1, 2020

Future Retail says Amazon dispute order not binding on company

US will 'vigorously defend' TikTok executive order despite ruling

Online giants will have to open ad archives to EU antitrust regulators: Antitrust panel chief

Tencent's Honor of Kings reports 100 million daily users, expands into new genres

Tencent claims record 100M daily users on mobile game Honor of Kings

At its five-year anniversary gala graced by celebrities, esports stars and orchestras, Tencent’s mobile game Honor of Kings said it has crossed 100 million daily active users. The title has not only broken user records but generated other unprecedented accomplishments along the way.

For one, it consistently ranks among the top-grossing mobile games worldwide, jostling with PUBG Mobile made by another Tencent studio Lightspeed & Quantum — gaming has long been the cash cow for Tencent, better known for its WeChat messenger. The brain behind Honor of Kings is TiMi Studios, which ramped up hiring in the U.S. this year to further global expansion.

The game is credited for popularizing the multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) category in China using clever designs like short sessions, friendly controls, esports integration, and social networking leverage, as games analyst Daniel Ahmad pointed out. The title has an unusually high female player base — around 50% — for a genre dominated by males.

TiMi focused on creating a MOBA that was tailored to the expectations of mobile players. Which included shorter session lengths, touch friendly controls and automated systems.

The game is great for beginners to the MOBA genre, but still requires skill to master. Broad appeal. pic.twitter.com/mSqMOKBEIc

— Daniel Ahmad (@ZhugeEX) November 1, 2020

Though not always seen as an original creator, Tencent pioneers monetization models for mobile games and can be Western studios’ sought-after partner. To name one, it helped develop the mobile version of Activision’s Call of Duty, which surpassed 250 million downloads in June.

Controversy has also arisen amid Honor of Kings’ fervor. A state newspaper chastised it for hooking young users and misrepresenting historical events. Tencent has since tightened age verification checks for players, now standard practice in China’s gaming industry.

TiMi unveiled its milestone at a time when Riot Games is testing a mobile version of League of Legends, widely seen as the desktop blockbuster that had inspired Honor of Kings in the first place. The overseas edition of Honor of Kings, called Arena of Valor, has had limited success outside Asia. It now comes the time for Riot, fully acquired by Tencent in 2015, to test its own interpretation, Wild Rift.

As part of the announcement, TiMi also revealed that it’s capitalizing on Honor of Kings for IP derivative works, including two new games in unspecified new genres, an anime, and a TV series.

Startup brands like the shoe company Thousand Fell are bringing circular economics to the fashion industry

Thousand Fell, the environmentally conscious, direct-to-consumer shoe retailer which launched last November, has revealed the details of the recycling program that’s a core component of its pitch to consumers.

The company, which has now sold enough shoes to start seeing its early buyers begin recycling them after ten months of ownership, expects to recycle roughly 3,000 pairs per quarter by 2021, with the capacity to scale up to 6,000 pairs of shoes.,

The recycling feature, through partnerships with United Parcel Service and TerraCycle, offers customers the option to avoid simply throwing out the shoes for $20 in cash that the company pays out upon receipt of the old shoes.

With the initiative, Thousand Fell joins a growing number of companies in consumer retail that are experimenting with various strategies to incorporate reuse into the life-cycle of their products. Nike operates a reuse a shoe program at some of its stores, which will collect used athletic shoes from any brand for recycling. And several companies are offering denim recycling drop-off locations to take old jeans and convert the material into other products.

What’s more, Thousand Fell’s recycling partner, TerraCycle, has developed a milkman model for reusing packaging to replace consumer packaged goods like dry goods, beverages, desserts and home and beauty products under its Loop brand (and in partnership with Kroger and Walgreens).

Across retail, zero waste packaging and delivery options (and companies emphasizing a more sustainable, circular approach to consumption) are attracting increased interest from investors across the board, with everyone from delivery companies to novel packaging materials attracting investor interest.

“Thousand Fell owns the material feeds and covers the cost of recycling, as well as the resale or reintegratoin of recycled material back into new shoes and the issuance of the $20 recycling cash that is sent back to the consumer once they recycle,” wrote Thousand Fell co-founder Stuart Ahlum, in an email.

Clothing and textiles account for 17% of all landfill waste and shoes are particularly wasteful. Shoes account for 10% of retail production capacity but about 25% of textile waste, according to Ahlum.

The company sells its environmentally friendly shoes for under $100, a price point that makes them more accessible to price-conscious consumers, according to Ahlum.

Through the program UPS will run shipping for the Thousand Fell sneaker recycling program and making its network of shipping locations — including within Staples stores — available for drop-off of Thousand Fell’s shoes.

With TerraCycle, Thousand Fell will ensure that the old sneakers will be sustainably recycled and diverted from landfills. UPS’ Ware2Go business is also providing fulfillment and warehousing services for Thousand Fell, the companies said in a statement earlier this week.

Meanwhile, TerraCycle and Thousand Fell are developing a closed loop process where old sneakers will be reintegrated into the supply chain to make new sneakers.

Through Thousand Fell, shoe buyers can track their purchase history and the carbon footprint of their sneakers at the company’s website — and register their sneakers once they’ve received them. The registration allows customers to initiate the recycling process at a drop off location or directly shipping their shoes back to TerraCycle.

“This enterprise partnership between UPS, TerraCycle, and Thousand Fell is the reverse logistics engine that powers the circular economy. It solves the critical problem of collecting worn products back from customers — at scale and at cost,” Ahlum wrote in an email.

Zego, which provides real-time communication tools for enterprises and runs a Zoom-style videoconferencing service called TalkLine, raises $50M led by Tencent (Zheping Huang/Bloomberg)

Zheping Huang / Bloomberg:

Zego, which provides real-time communication tools for enterprises and runs a Zoom-style videoconferencing service called TalkLine, raises $50M led by Tencent — - Zego offers real-time voice, video technology solutions — Rival Agora raised $350 million in U.S. listing this year

IBPS Specialist Officer IX Recruitment 2020 – Apply for 647 Posts

A look at the key social media feedback loops that help Trump, where his high-profile influencers and rank-and-file followers push messages both to and from him (Washington Post)

Washington Post:

A look at the key social media feedback loops that help Trump, where his high-profile influencers and rank-and-file followers push messages both to and from him — Researchers say the online feedback loop between Trump, high-profile influencers and rank-and-file followers is more dangerous than Russian disinformation.

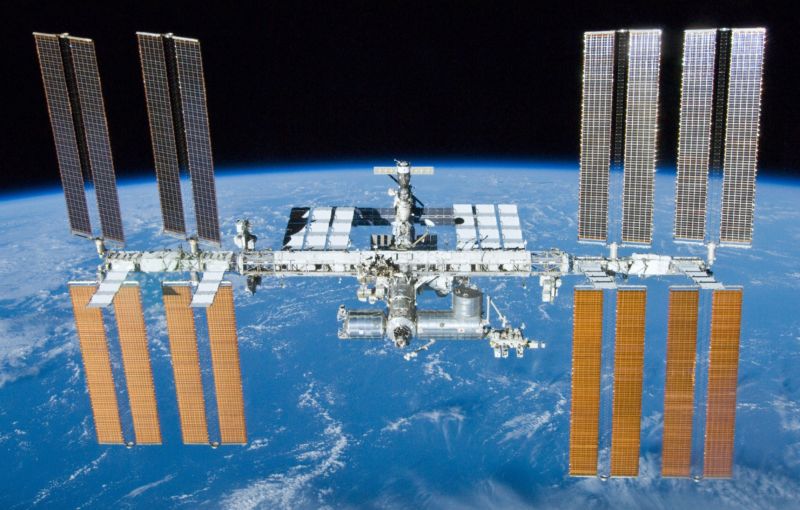

After 20 years of service, the Space Station flies into an uncertain future

Enlarge / The essentially complete International Space Station in 2010, as seen by space shuttle Atlantis. (credit: NASA)

The Cold War had been concluded for less than a decade when NASA astronaut Bill Shepherd and two Russian cosmonauts, Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko, crammed themselves into a Soyuz spacecraft and blasted into orbit on Halloween, 20 years ago.

Two days later their small spacecraft docked with the International Space Station, then a fraction of the size it is today. Their arrival would herald the beginning of what has since become 20 years of continuous habitation of the laboratory that NASA, leading an international partnership, would continue to build for another decade.

Born of a desire to smooth geopolitical tensions in the aftermath of the great conflict between the United States and Soviet Union, the space station partnership has more or less succeeded—the station has remained inhabited despite the space shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, and later, nearly a decade of no US space transportation. NASA, Roscosmos, and the European, Japanese, and Canadian partners have been able to rely on one another.

How claims of voter fraud were supercharged by bad science

During the 2016 primary season, Trump campaign staffer Matt Braynard had an unusual political strategy. Instead of targeting Republican base voters—the ones who show up for every election—he focused on the intersection of two other groups: people who knew of Donald Trump, and people who had never voted in a primary before. These were both large groups.

Because of his TV career and ability to court controversy, Trump was already a household name. Meanwhile, about half America’s potential voters, nearly 100 million people, don’t vote in presidential elections, let alone primaries. The overlap between the groups was significant. If Trump could mobilize even a small percentage of those people, he could clinch the nomination, and Braynard was willing to put in the work.

His strategy, built from polls, research, and studies of voting behavior, focused on two goals in particular. The first was registering, engaging, educating, and turning out non-voters, the largest electoral bloc in the country and one that’s regularly ignored. One recent survey of 12,000 “chronic non-voters” suggests they receive “little to no attention in national political conversations” and remain “a mystery to many institutions.”

One way to turn out potentially sympathetic voters would be to use a call center to remind them, which would also help with his second goal: to investigate and expose voter fraud.

“If you’re trying to do systematic voter fraud, you’re going to look for people who haven’t or are not going to cast their ballot,” he told me in a recent interview, “because if you do cast a ballot for them and they do show up at the polling place, that’s going to set up a red flag.”

So the plan was that after the election, the call centers would contact a sample of the people in the state who had voted for the first time to confirm that they had actually cast a ballot.

Not only was pursuing voter fraud popular with prospective donors, Braynard says, but it was also an endeavor supported by the academic literature. “I believe it’s been documented, at least scientifically in some peer-reviewed studies, that at least one senator in the last 10 years was elected by votes that aren’t legal ballots,” he says.

This single voter fraud study has become canonical among conservative, and many of today’s other claims of fraud—such as through mail-in voting—also trace back to it.

A study like this does in fact exist, and it and is peer-reviewed. In fact, it goes even further than Braynard remembers. Published in 2014 by Jesse Richman, a political science professor at Old Dominion University, it argues that illegal votes have played a major role in recent political outcomes. In 2008, Richman argued, “non-citizen votes” for Senate candidate Al Franken “likely gave Senate Democrats the pivotal 60th vote needed to overcome filibusters in order to pass health care reform.”

The paper has become canonical among conservatives. Whenever you hear that 14% of non-citizens are registered to vote, this is where it came from. Many of today’s other claims of voter fraud—such as through mail-in voting—also trace back to this study. And it’s easy to see why it has taken root on the right: higher turnout in elections generally increases the number of Democratic voters, and so proof of massive voter fraud justifies voting restrictions that disproportionately affect them.

Academic research on voting behavior is often narrowly focused and heavily qualified, so Richman’s claim offered something exceedingly rare: near certainty that fraud was happening at a significant rate. According to his study, at least 38,000 ineligible voters—and perhaps as many as 2.8 million—cast ballots in the 2008 election, meaning the “blue wave” that put Obama in office and expanded the Democrats’ control over Congress would have been built on sand. For those who were fed up with margins of error, confidence intervals, and gray areas, Richman’s numbers were refreshing. They were also very wrong.

The data dilemma

If you want to study how, whether, and for whom people are going to vote, the first thing you need is voters to ask. Want to reach them by phone? Good luck calling landlines: very few people pick up. You might have a better chance with cell phones, but don’t expect much.

Telephone surveys are “barge in” research says Jay H. Leve, the CEO of SurveyUSA, a polling firm based in New Jersey. These phone polls, he says, happen at a time that’s convenient to the pollster, and “to hell with the respondent.” For that reason, the company aims to limit calls to four to six minutes, “before the respondent begins to feel like he or she is being abused.” Online surveys are preferable because respondents can complete them when they want, but it’s still hard to motivate people. For that reason, many survey companies offer something in return for people’s opinion, typically points that can be exchanged for gift cards.

Even if you’ve found participants, you want to make sure you’re asking good questions, says Stephen Ansolabehere, a government professor at Harvard. He is principal investigator of the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), a national survey of more than 50,000 people about demographics, general political attitudes, and voting intentions—and the data set used in Jesse Richman’s voter fraud study. It’s easy to generate bias in your results by wording your survey questions poorly, says Ansolabehere.

“We’ll try and be literal and give brief descriptions, and we generally don’t do things too adjectivally,” Ansolabehere says. But what about when the bill you’re asking about is called something inflammatory, like the “Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act?” “We don’t use that title,” he says.

Another problem with opinion polling is that what somebody thinks doesn’t really matter if it’s not going to translate into a vote. That means you have to figure out who will actually show up to the polls.

Here, demographic data is helpful. Women vote slightly more than men. White people vote more than people of color. Those 65 and older vote at rates roughly 50% higher than those 18 to 29, and advanced degree holders up to nearly three times as often as those without a high school diploma.

However, even if you ladle on the enticements, some demographic groups are simply less likely to respond to survey requests, which means you’ll need to adjust the numbers coming out of your survey group. Most polling firms do this by amplifying the responses they get from underrepresented groups: a survey with a small sample of Hispanic voters, say, might weight their responses more heavily if trying to predict behavior in a battleground state like Arizona, where 24% of voters are Latino.

One 2016 presidential poll conducted included a young Black man living in the Midwest who supported Trump. Because he represented several harder-to-reach categories—young, minority, male—his responses were dramatically over-indexed.

But beware: this weighting can backfire.

One 2016 presidential poll conducted by the University of Southern California and the Los Angeles Times recruited 3,000 respondents from across America, including a young Black man living in the Midwest who turned out to be a Trump supporter. Because he represented several harder-to-reach categories—young, minority, male—his responses were dramatically over-indexed. This ended up throwing the numbers off: at one point the survey estimated Trump’s support among Black voters at 20%, largely on the basis of this one man’s responses. A post-election analysis put that number at 6%.

The media, grasping for certainty, missed the error margins of the study and reached for the headline figures that amplified these overweighted responses. As a result, the survey team— which had already made raw data, weighting schemes, and methodology public—stopped releasing sub-samples of their data to prevent their study being distorted again. Not all researchers are as concerned about potential misinterpretation of their work, however.

An academic controversy

Until Richman’s 2014 paper, the virtual consensus among academics was that non-citizen voting didn’t exist on any functional level. Then he and his coauthors examined CCES data and claimed that such voters could actually number several million.

Richman asserted that the illegal votes of non-citizens had changed not only the pivotal 60th Senate vote but also the race for the White House. “It is likely though by no means certain that John McCain would have won North Carolina were it not for the votes for Obama cast by non-citizens,” the paper says. After its publication, Richman then wrote an article for the Washington Post with a similarly provocative headline that focused on the upcoming 2014 midterms: “Could non-citizens decide the November election?”

Unsurprisingly, conservatives ran with this new support for their old narrative and have continued to do so. The study’s fans include President Trump, who used it to justify the creation of his short-lived and failed commission on voter fraud, and whose claims about illegal voting are now a centerpiece of his campaign.

But most other academics saw the study as an example of methodological failure. Ansolabehere, whose CCES data Richman relied on, coauthored a response to Richman’s work titled “The Perils of Cherry Picking Low-Frequency Events in Large Sample Sizes.”

For starters, he argued, the paper overweighted the non-citizens in the survey—just as the Black Midwestern voter was overweighted to produce an illusion of widespread Black support for Trump. This was especially problematic in Richman’s study, wrote Ansolabehere, when you consider the impact that a tiny number of people who were misclassified as non-citizens would have on the data. Some people, said Ansolabehere, had likely misidentified themselves as ineligible to vote in the 2008 study by mistake—perhaps out of sloppiness, misunderstanding, or just the rush to accumulate points for gift cards. Critically, nobody who had claimed to be a non-citizen in both the 2010 survey and the follow-up in 2012 had cast a validated vote.

Nearly 200 social scientists echoed Ansolabehere’s concerns in an open letter, but for Harold Clarke, then editor of the journal that published Richman’s paper, the blowback was hypocritical. “If we were to condemn all the papers on voting behavior that have made claims about political participation based on survey data,” he says, “well, this paper is identical. There’s no difference whatsoever.”

As it turns out, survey data does contain a lot of errors—not least because many people who say they voted are lying. In 2012, Ansolabehere and a colleague discovered that huge numbers of Americans were misreporting their voting activity. But it wasn’t the non-citizens, or even the people who were in Matt Braynard’s group of “low propensity” voters.

Instead, found the researchers, “well-educated, high-income partisans who are engaged in public affairs, attend church regularly, and have lived in the community for a while are the kinds of people who misreport their vote experience” when they haven’t voted at all. Which is to say: “high-propensity” voters and people likely to lie about having voted look identical. Across surveys done over the telephone, online, and in person, about 15% of the electorate may represent these “misreporting voters.”

Ansolabehere’s conclusion was a milestone, but it relied on something not every pollster has: money. For his research, he contracted with Catalist, a vendor that buys voter registration data from states, cleans it, and sells it to the Democratic Party and progressive groups. Using a proprietary algorithm and data from the CCES, the firm validated every self-reported claim of voting behavior by matching individual survey responses with the respondents’ voting record, their party registration, and the method by which they voted. This kind of effort is not just expensive (the Election Project, a voting information source run by a political science professor at the University of Florida, says the cost is roughly $130,000) but shrouded in mystery: third-party companies can set the terms they want, including confidentiality agreements that keep the information private.

In a response to the criticism of his paper, Richman admitted his numbers might be off. The estimate of 2.8 million non-citizen voters “is itself almost surely too high,” he wrote. “There is a 97.5% chance that the true value is lower.”

Despite this admission, however, Richman continued to promote the claims.

In March of 2018, he was in a courtroom testifying that non-citizens are voting en masse.

Kris Kobach, the Kansas secretary of state, was defending a law that required voters to prove their citizenship before registering to vote. Such voter ID laws are seen by many as a way to suppress legitimate votes, because many eligible voters—in this case, up to 35,000 Kansans—lack the required documents. To underscore the argument and prove that there was a genuine threat of non-citizen voting, Kobach’s team hired Richman as an expert witness.

Paid a total of $40,663.35 for his contribution, Richman used various sources to predict the number of non-citizens registered to vote in the state. One estimate, based on data from a Kansas county that was later proved to be inaccurate, put the number at 433. Another, extrapolated from CCES data, said it was 33,104. At the time, there were an estimated 115,000 adult residents in Kansas who were not American citizens—including green card holders and people on visas. By Richman’s calculations, that would mean nearly 30% of them were illegally registered to vote. Overall, his estimates ran from roughly 11,000 to 62,000. “We have a 95% confidence that the true value falls somewhere in that range,” he testified.

The judge ended up ruling that voter ID laws were unconstitutional. “All four of [Richman’s] estimates, taken individually or as a whole, are flawed,” she wrote in her opinion.

Unseen impact

One consequence of this unreliable data—from citizens who lie about their voting record to those who mistakenly misidentify themselves as non-citizens—is that it further diverts attention and resources from the voters who lie outside traditional polling groups.

“For the [low-propensity] crowd it is a vicious cycle,” wrote Matt Braynard in his internal memo for the Trump campaign. “They don’t get any voter contact love from the campaigns because they don’t vote, but they don’t vote because they don’t get any voter contact. It is a persistent state of disenfranchisement.”

Campaigns focus on constituents who are likely to vote and likely to give money, says Allie Swatek, director of policy and research for the New York City Campaign Finance Board. She experienced this bias firsthand when she moved back to New York in time for the 2018 election. Though there were races for US Senate, governor, and state congress, “I received nothing in the mail,” she says. “And I was like, ‘Is this what it’s like when you have no voting history? Nobody reaches out to you?”

According to the Knight Foundation’s survey of non-voters, 39% reported that they’ve never been asked to vote—not by family, friends, teachers, political campaigns, or community organizations, nor at places of employment or worship. However, that may be changing.

Braynard’s mobilization strategy played a role in the 2018 campaign for governor of Georgia by Democrat Stacey Abrams. She specifically targeted low-propensity voters, especially voters of color, and though she ultimately lost that race, more Black and Asian voters turned out that year than for the presidential race in 2016. “Any political scientist will tell you this is not something that happens,” wrote Abrams’s former campaign manager in a New York Times op-ed. “Ever.”

But even if campaigns and experts try to break these cycles—by cleaning their data, or by targeting non-voters—there’s a much more dangerous problem at the heart of election research: it is still susceptible to those operating in bad faith.

Backtracking claims

I asked Richman earlier this summer if we should trust the sort of wide-ranging numbers he gave in his study, or in his testimony in Kansas. No, he answered, not necessarily. “One challenge is that people want to know what the levels of non-citizen registration and voting are with a level of certainty that the data at hand doesn’t provide,” he wrote me in an email.

In fact, Richman told me, he “ultimately agreed” with the judge in the Kansas case despite the fact that she called his evidence flawed. “On the one hand, I think that non-citizen voting happens, and that public policy responses need to be cognizant of that,” he told me. “On the other hand, that doesn’t mean every public policy response makes an appropriate trade-off between the various kinds of risk.”

Behind the academic language, he’s saying essentially what every other expert on the subject has already said: fraud is possible, so how do we balance election security with accessibility? Unlike his peers, however, Richman reached that conclusion by first publishing a paper with alarmist findings, writing a newspaper article about it, and then testifying that non-citizen voting was rampant, maybe, despite later agreeing with the decision that concluded he was wrong.

Whatever Richman’s reasons for this, his work has helped buttress the avalanche of disinformation in this election cycle.

Throughout the 2020 election campaign, President Trump has continued to make repeated, unfounded claims that vote-by-mail is insecure, and that millions of votes are being illegally cast. And last year, when a ballot harvesting scandal hit the Republican Party in North Carolina and forced a special election that led to a Democratic win, one operative made an appearance on Fox News to accuse the left of encouraging an epidemic of voter fraud.

“The left is enthusiastic about embracing this technique in states like California,” he said. “Voter fraud’s been one of the left’s most reliable voter constituencies.”

The speaker? Matt Braynard.

However, Braynard is unlike some voter fraud evangelists, for whom finding no evidence of fraud is simply more evidence of a vast conspiracy. He at least purports to be able to change his mind on the basis of new facts. This suggests that there may be a way out of this current situation, where we project our own assumptions onto the uncertainty inherent in voting behavior.

After leaving the Trump campaign, he founded Look Ahead America, a nonprofit dedicated to turning out blue-collar and rural voters and to investigating voter fraud. As part of the group’s work, he and 25 other volunteers served as poll watchers in Virginia in 2017.

The process wasn’t as transparent as he would’ve liked. He wasn’t allowed to look over poll workers’ shoulders, and there were no cameras to photograph voters as they cast their ballots. But even though he wasn’t absolutely certain that the election was clean, he was still confident enough to issue a press release the following day.

“At least where we were present, the local election officials faithfully followed the lawful procedures,” LAA’s statement said. “We did observe a few occasions where polling staff could benefit from better education on the relatively recent voter ID laws. Nonetheless, they worked diligently to ensure the election laws were followed.”

https://ift.tt/3erB2pj https://ift.tt/321TJL4WhatsApp could release Disappearing Messages feature in a future update

It looks like we’ll soon be getting a ‘Disappearing Messages’ feature on WhatsApp. As per a report on Wabetainfo, WhatsApp is looking at releasing the feature in a future update. So what exactly are disappearing messages. Well, If you receive a bunch of messages and don’t read them for about 7 days, those messages will disappear. Users will have the option to enable this feature when it does eventually arrive.

A key thing to remember though is that when you do enable the feature, there is no option to customize the time frame for when the messages are deleted. All unread messages will expire after 7 days. Although, if you do not clear your notification panel, the messages will still be available to be read.

The cited source in the Wabetainfo report goes on to say, “When you reply to a message, the initial message is quoted. If you reply to a disappearing message, the quoted text might remain in the chat after seven days. If a disappearing message is forwarded to a chat with disappearing messages off, the message won’t disappear in the forwarded chat.”. You can still backup your chats on Google Drive and view them there but you will not be able to restore those particular chats once the Disappearing Messages feature is enabled. The Disappearing Messages feature will be hitting for iOS, Android, KaiOS, and Web/Desktop users as well.

Eta forms, tying Atlantic record for most tropical systems in a season

Enlarge / Tropical Storm Eta's satellite appearance on Sunday morning, Nov. 1.

Late on Saturday night, the National Hurricane Center upgraded a tropical depression in the Caribbean Sea to become Tropical Storm Eta.

This is the 28th named storm of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, and ties 2005 for the most tropical storms and hurricanes to be recorded in a single season. The Atlantic "basin" covers the Atlantic ocean north of the equator, as well as the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea.

Eta poses a distinct threat to land. Although the storm's track remains ultimately uncertain, Eta should move somewhat due west for the next few days, likely strengthening to become a hurricane before landfall in Nicaragua by Tuesday evening or Wednesday. As it will be a slow-moving, meandering storm, Eta will produce a prodigious amount of rainfall, with up to 30 inches possible over parts of Nicaragua and Honduras. This will lead to significant flooding, with landslides and swollen rivers.

Electricians are flocking to regions around the US to build data centers, as AI shapes up to be an economy-bending force that creates boom towns (New York Times)

New York Times : Electricians are flocking to regions around the US to build data centers, as AI shapes up to be an economy-bending force...

-

Jake Offenhartz / Gothamist : Since October, the NYPD has deployed a quadruped robot called Spot to a handful of crime scenes and hostage...

-

Answers to common questions about PCMag.com http://bit.ly/2SyrjWu https://ift.tt/eA8V8J