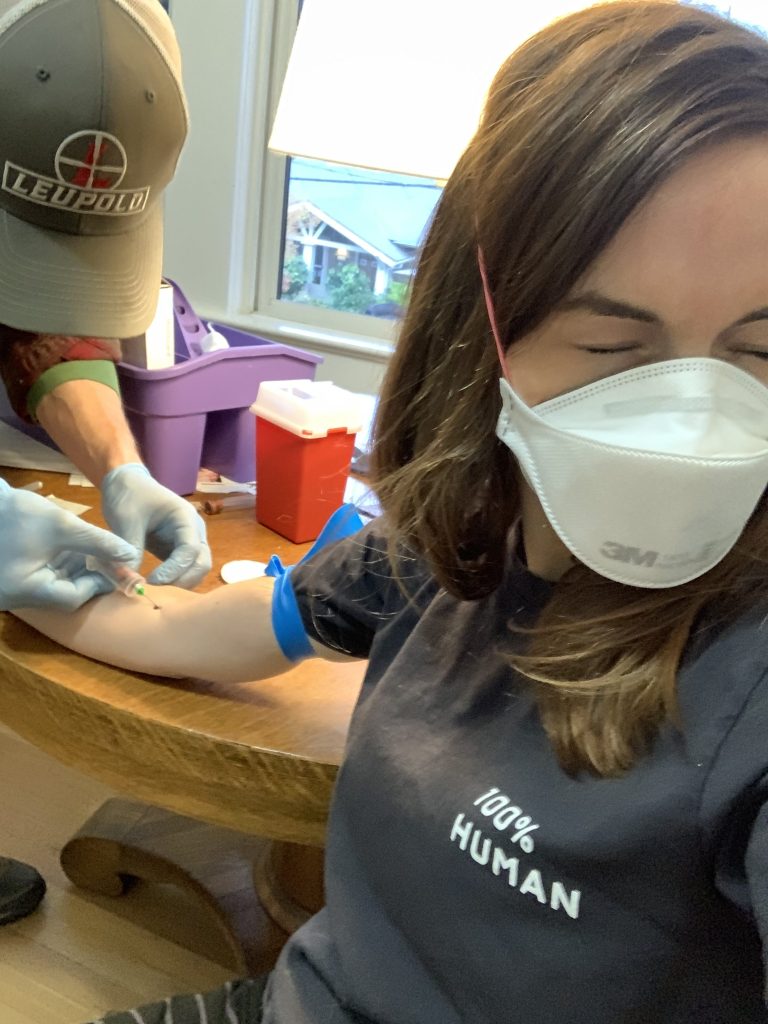

In Portland, Oregon, earlier this spring, a programmer named Ian Hilgart-Martiszus pulled out a needle and inserted it into the arm of social worker Alicia Rowe as she squinted and looked away. He was testing for antibodies to the coronavirus. He’d gathered 40 friends and friends of friends, and six homeless men too.

As a former lab technician, Hilgart-Martiszus knew how to do it. Despite extensive debate over the accuracy of blood tests for coronavirus antibodies and how they should be used, by March anyone with a credit card and some savvy could order “research only” supplies online and begin testing.

“I am just doing it at home. This is total citizen science,” he says. Pretty much everyone who has had the sniffles or a fever in the last few months wants to know if was really covid-19.

On April 6, Hilgart-Martiszus posted results of what he dubbed the nation’s “first community serum testing” survey for covid-19, complete with figures and a description of how he did it. He’d beaten out big medical centers by weeks. His data indicated one positive case and three suspected ones.

The DIY effort put him, for a few days, into the forefront of the search for antibodies, blood proteins which form in response to covid-19 and are a telltale indication you’ve been infected. There are now dozens of surveys under way by blood banks and hospitals, and Quest Diagnostics has an online portal where people can try to make an appointment for a blood draw. A physician still has to approve the order.

Just one month ago, though, this type of information was hard to come by. Hilgart-Martiszus, annoyed by criticism of President Trump’s coronavirus response by what he calls the media “echo chamber,” figured that he would try to “fill the void” with actual data. He adds that he is skeptical of big government and “political officials comfortably receiving a salary and advocating to keep the economy closed.”

The mayor of Portland, Ted Wheeler, he slams as #trashyted.

Hilgart-Martiszus, whose day job is in real-estate planning for a sporting goods chain, first built a computer dashboard in March to predict hospitalizations in Oregon. He emailed a copy to his boss, who told him the company didn’t want to be involved.

By then, though, Hilgart-Martiszus was developing bigger plans. By March, scientific supply companies had begun advertising kits to probe human blood serum for antibodies to the distinctive “spike” protein on the virus. He paid $550 each to get some from the Chinese supplier GenScript.

Most research is carried out by universities or companies under a firm framework of rules. Two weeks after Hilgart-Martiszus posted his results, for instance, his old employer, Providence Health Care services, announced its own much larger serum study, drawing blood from 1,000 people in one day, according to news reports. While Hilgart-Martiszus’s study didn’t have the bells and whistles, or any kind of approval, he couldn’t resist reminding them who was first: “Looks like my old research institute will publish the second antibody study in Oregon. Can’t wait to see how their results compare.”

In Oregon drawing someone else’s blood is legal for anyone who knows how, says Charles “Derris” Hurley, a former pharmacist who says he fronted Hilgart-Martiszus $2,000 to purchase testing supplies. “I said, ‘Let’s go ahead and try this—if we learn something we learn something, and if we don’t we don’t,’” he says. “We are of the attitude that everyone should be tested.”

To take part in the project, Hurley drew blood from his wife, Jan Spitsbergen, a PhD microbiologists who tends zebrafish at Oregon State University, and she drew his. “She was a lot better at it,” he says.

Hilgart-Martiszus used the most accurate kind of antibody test, called an ELISA, which requires some equipment and know-how. He put the blood from his volunteers into special tubes, letting it clot for about 45 minutes. Next he spun it in a centrifuge for 10 minutes and used a pipette to suction off the serum, a clear liquid where the antibodies would be. Then he added dilution buffer and let it incubate with the chemicals he’d bought online on a plastic plate with 96 wells. The liquid would change color if antibodies were present.

To measure the readout from the wells, he needed a machine to scan the plate, which he managed to borrow from a nearby university. This particular test looks for IGG antibodies, a type that would be expected to appear about two weeks after infection.

In 40 tests, it was Hurley whose blood showed the strongest signal for antibodies to the virus—many times higher than anyone else’s. “If you look at Ian’s printout, I am the one that stands out like a sore thumb,” says Hurley.

It was the potential explanation for a mystery ailment Hurley suffered in mid-December. He’d come down with an unusual cold. He felt fatigued and had red eyes. Then his wife got sick in January and stayed in bed for two weeks. Plus, they’d had a Chinese exchange student living with them at the time. “We started talking more and more—‘We need to have some kind of test, something is wrong,’” he recalls.

Hurley believes he had covid-19, but if he did, that would mean the illness was circulating in the US a month earlier than is widely known (the first official American case was recorded in January near Seattle). As of May 2, the Oregon Health Authority says, there have been 2,579 cases and 104 deaths in the state, making it among those least affected.

Hurley says his positive result is not enough for him to resume his normal routine. “I follow social distancing,” he says. “I guess I want to have more verification and have some idea how long immunity lasts.”

Hilgart-Martiszus asked everyone to tell him if they’d been sick. That included Rowe, the social worker from Portland. “I had a cold in February, and I really hoped that I had gotten it out of the way, but no such luck.” She came up negative.

Demand for antibody tests remains high. After Hilgart-Martiszus posted his results to the web, “he was inundated with requests from all over the world,” says Spitsbergen. A hospital wanting to test its medical staff reached out to him. So did a fire department wanting to test 100 people.

With all the new attention, Hilgart-Martiszus says he’s trying to play by the rules and is not collecting any more blood at the moment. He’s instead working with Oregon State University to create a larger, more formalized study, with approval from an ethics board. He launched a crowdfunding campaign and a website where he’s developing plans to let anyone send in blood for testing.

“I told the first group, don’t take this as a clinical diagnosis—it’s not. It’s research,” he says. “I just pushed it out there.” Now he’s telling people he can’t test them right away, at least until he gets his paperwork in order. “It sucks to wait to help people,” he says, “but with all of the regulations, it’s too risky to test strangers.”

https://ift.tt/2KSrghF https://ift.tt/2KTwh9R