At some point covid-19 will be vanquished. By early April some 50 potential vaccines and nearly 100 potential treatment drugs were in development, according to the Milken Institute, and hundreds of clinical trials were already registered with the World Health Organization.

Even with all these efforts, a vaccine is expected to take at least 12 to 18 months to bring to market. A treatment may arrive sooner—one company, Regeneron, says it hopes to have an antibody drug in production by August—but making enough of it to help millions of people could take months more.

It could all be over more quickly if certain existing drugs, already known to be safe for other uses, prove effective in treating covid-19. Trials are now under way; we should know by the summer. On the flip side, it may be that only a vaccine delivers the knockout blow, and even then, we still don’t know how long one will stay effective as the virus mutates.

This is why everything feels unmoored and why everybody is stressed: because we can no longer predict what will be allowed and what will not a week, a month, or 12 months hence.

That means we have to prepare for a world in which there is no cure and no vaccine for a long time. There is a way to live in this world without staying permanently shut indoors. But it won’t be a return to normal; this will be, for Westerners at any rate, a new normal, with new rules of behavior and social organization, some of which will probably persist long after the crisis has ended.

In recent weeks a consensus has started to build among various groups of experts on what this new normal might look like. Some parts of the strategy will reflect the practices of contact tracing and disease monitoring adopted in the countries that have dealt best with the virus so far, such as South Korea and Singapore. Other parts are starting to emerge, such as regularly testing massive numbers of people and relaxing movement restrictions only on those who have recently tested negative or have already recovered from the virus— if indeed those people are immune, which is assumed but still not certain.

This will entail a considerable degree of surveillance and social control, though there are ways to make it less intrusive than it has been in some countries. It will also create or exacerbate divisions between haves and have-nots: those who have work that can be done from home and those who don’t; those who are allowed to move about freely and those who aren’t; and, especially in the US and other countries without universal health coverage, those who have medical care and those who lack it. (Though Americans can now get coronavirus tests for free by law, they may still wind up with hefty bills for related tests and treatment.)

This new social order will seem unthinkable to most people in so-called free countries. But any change can quickly become normal if people accept it. The real abnormality is how uncertain things are. The pandemic has undercut the predictability of normal life, the sheer number of things we always assume we will still be able to do tomorrow. That is why everything feels unmoored, why the economy is collapsing, why everybody is stressed: because we can no longer predict what will be allowed and what will not a week, a month, or three or six or 12 months hence.

Getting to normal, therefore, is not so much about getting back the old normality as it is about getting back the ability to know what is going to happen tomorrow. And it’s becoming increasingly clear what’s needed to achieve that kind of predictability. What we can’t predict, yet, is how long it will take political leaders to do what it takes to get there.

The background

First, let’s look at why simply waiting for a drug or vaccine isn’t a practical option.

One feature of the covid-19 pandemic is the speed with which the unthinkable has become the obvious. In mid-March, the British government was still advocating for letting most people go about more or less their normal daily business, while only the sick and the especially vulnerable isolated themselves. It changed tack rapidly after researchers at Imperial College London published a study showing the policy would lead to as many as 250,000 deaths in the UK.

That study made the case for what almost everyone now agrees is essential: imposing social distancing on as much of the population as possible. This is the only way to “flatten the curve,” or slow the spread of the virus enough to prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed, as they have been in Italy, Spain, and New York City. The goal is to keep the pandemic ticking along at a manageable level until either enough people have had covid-19 to create “herd immunity”—the point at which the virus is starting to run out of new people to infect—or there’s a vaccine or cure.

Waiting for herd immunity is not an idea most experts take seriously. But no matter what the final outcome, some degree of social distancing has to remain in place until we get there. A strict lockdown can slow new infections to a trickle, as it did in China’s Hubei province, but as soon as measures are relaxed, the infection rate starts to rise again.

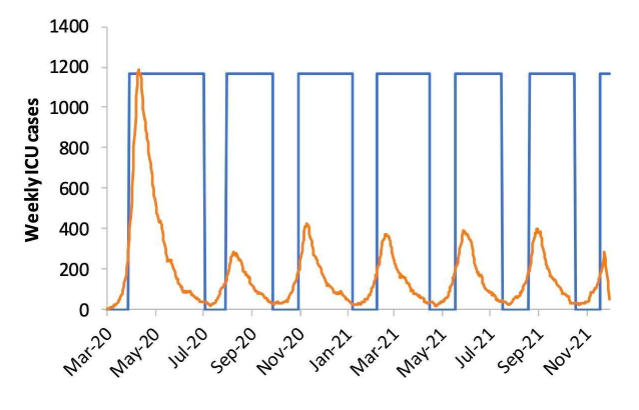

In their report on March 16, the researchers at Imperial College proposed a way of alternating between stricter and looser regimes: impose widespread social distancing measures every time admissions to intensive care units (ICUs) start to spike, and relax them each time admissions fall. Here’s how that looks in a graph.

The orange line is ICU admissions. Each time they rise above a threshold—say, 100 per week—the country would close all schools and most universities and adopt social distancing. When they drop below 50, those measures would be lifted, but people with symptoms or whose family members have symptoms would still be confined at home.

What counts as “social distancing”? The researchers define it as “All households reduce contact outside household, school, or workplace by 75%.” That doesn’t mean you should feel free to go out with your friends once a week instead of four times. It means if everyone does everything they can to minimize social contact, then on average, the number of contacts is expected to fall by 75%.

Under this model, the researchers concluded, both social distancing and school closures need to be in force some two-thirds of the time— roughly two months on and one month off—until a vaccine or cure is available. They noted that the results are “qualitatively similar for the US.”

The researchers also modeled various less stringent policies, but all of them came up short. What if you only isolate the sick and the elderly, and let other people move around freely? You’d still get a surge of critically ill people at least eight times bigger than the US or UK healthcare system can handle. What if you lock everybody down for just one extended period of five months or so? No good—as long as a single person is infected, the pandemic will ultimately break out all over again. Or what if you set a higher threshold for the number of ICU admissions that triggers tighter social distancing? It would first mean accepting that many more patients would die, but it also turns out that it makes little difference: even in the least restrictive of the Imperial College scenarios, we’re shut in more than half the time. That means the economic paralysis lasts until there’s a vaccine or cure.

The tools

Those scenarios, however, assumed that being shut in applies equally to everyone. But not everyone is equally at risk, or risky. The key to getting to normal will be to establish systems for discriminating—legally and fairly—between those who can be allowed to move around freely and those who must stay at home.

Assorted proposals now coming out of bodies such as the American Enterprise Institute, the Center for American Progress, and Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, describe how this might be done. The basic outlines are all similar.

First, keep as many people as possible at home until the rate of infections is well under control. Meanwhile, massively ramp up testing capacity, so that once the country is ready to relax social distancing rules, anybody who asks for a test—and some who don’t—can take one and get the result within hours or, ideally, minutes. This has to include testing both for the virus, in order to detect people who are currently sick even if they don’t have symptoms, and for antibodies, in order to find people who have had the disease and are now immune.

People who test positive for antibodies might be granted “immunity passports,” or certificates to let them move freely; Germany and the UK have already said they plan to issue such documents. People who test negative for the virus would be allowed to move around too, but they would have to get retested regularly and agree to have their cell phone’s location tracked. This way they could be alerted if they come into contact with anyone who has been infected.

This new social order will seem unthinkable to most people in so-called free countries

This sounds Big Brotherish, and it can be: in Israel, such automated monitoring and contact tracing is being done by the domestic intelligence agency, using surveillance tools created for tracking terrorists. But there are less intrusive ways of doing it.

The Safra Center, for example, outlines various schemes for “peer-to-peer tracking,” in which an app on your phone swaps encrypted tokens via Bluetooth with any other phones that spend some minimum period of time nearby. If you test positive for the virus, you put that information into the app. Using the tokens your phone has collected in the past few days, it sends alerts to those people to self-isolate or go get tested. Your actual location doesn’t have to be tracked, only the anonymized identities of the people you’ve been near. Singapore uses a peer-to-peer tracking app called TraceTogether, which sends the infection alerts to the health ministry, but—in principle at least— such a system can be set up with no centralized record-keeping at all.

There also needs to be nationwide data-gathering and analysis to better understand how the virus is spreading and spot high-risk areas that might need more testing or medical resources, or another quarantine. This strategy has to include serological surveys—random testing for antibodies to find out how widely the virus has already spread. Some other ways to gauge its prevalence without spying on people directly might be to crowdsource the information using sites like covidnearyou.org, infer it from the volume of Google searches for covid-19 symptoms in different places, or even look for the virus in samples of sewage.

It’s also important to make sure people who have tested positive or been exposed are staying in quarantine. This, however, seems hard to do without more direct surveillance. Countries like Singapore and South Korea use various means, such as making people share their location via WhatsApp or download a specialized tracking app. Whether the US or European countries could impose (let alone enforce) that kind of control isn’t clear. Without it, we have to rely on people to be responsible citizens and self-isolate when necessary.

The point is, there are more and less creepy ways of doing all this, and the crisis could catalyze a broader conversation about how to use people’s data for the collective good while protecting the individual.

The hurdles

Regardless of the methods chosen, the goal is the same: after a couple of months of shutdown, to begin selectively easing restrictions on movement for people who can show they’re not a disease risk. With good enough testing capacity, data collection, contact tracing, enforcement of or adherence to quarantines, and coordination between the federal, state, and local governments, local outbreaks might be contained before they spread and force another national shutdown.

Gradually, more and more people would be able to return to some semblance of normality. It would still be a far cry from the packed bars and sports arenas of the past, but it would be a less unbearable way to wait for the discovery of a vaccine or cure. More important, the economy could start ticking back to life.

This depends on a lot of things going right, though. First, the initial shutdown probably needs to be harsher than it currently is in the US. At the time of writing some US states still had no stay-at-home orders, few cities were enforcing those orders, and there were no restrictions on travel between cities or states. In China, by contrast, cities in Hubei province spent some two months in strictly enforced lockdown, with public transport cut off and inter-city movement restricted.

Second, by some estimates, millions of virus tests a day, promptly performed, may be required to properly keep tabs on the pandemic in the US. By April 8 the country was testing around 150,000 people a day, and many results were taking more than a week to come back.

Third, testing for antibodies is still in its infancy, and most of the tests currently in development still return fairly high rates of both false positives and false negatives, according to the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. A plan to order millions of home test kits for the UK ran into trouble after experts found they might work as little as half the time.

Fourth, the US in particular has precious little coordinated national strategy. The chaotic management of the crisis by the Trump administration, the separation of powers between the federal government and the states, and the fragmented nature of privatized health care make it unclear how systems for automated contact tracing, quarantine enforcement, or immune certification will emerge.

That means a reopening of the US in June is optimistic, to say the least, and a reopening by April 30, as President Donald Trump was still hoping for in early April, is a fantasy. But Trump, along with his alter ego, Fox News, has gradually and reluctantly been moving toward a more realistic stance about the pandemic. By the end of March the White House had adopted projections of the death toll in line with those of many experts, even if those projections still assumed stricter social distancing measures than the federal government is currently calling for. As the pandemic spreads further into the country and starts to pummel the more Republican-leaning states, the president’s interests may start to align more closely with those of the country as a whole.

The outcome

This, then, is what passes for optimism in these grim times: the hope that while the days are still warm, and after tens if not hundreds of thousands of lives have been lost that could have been saved with quicker action, some of us will be able to start crawling out into the sunlight. We’ll emerge into a world in which people give each other wide berths and suspicious looks, where those public venues still in business allow only the thinnest crowds to congregate, and where a system of legal segregation determines who can enter them. Millions will still be out of work and struggling to get by, and people will watch nervously for signs of a new flare-up near them.

But as you contemplate that future, spare a thought for the billions of people in the world for whom even social distancing and basic hygiene are unaffordable luxuries, let alone testing, treatment, and technologically advanced governments. The pandemic will roar through the slums of the world’s poorest countries like fire through sawdust. In their considerably younger populations, it will probably be less deadly than in the rich world. But an unchecked pandemic there may also oblige other countries to keep their borders closed for longer to protect their own populations.

A miracle may still happen. Perhaps a readily available drug will work. Perhaps testing will show that the virus is far more widespread and less deadly than we thought. It’s worth hoping for these things, but we can’t bank on them. What we can expect is to have an increasingly clear picture, as the days go by, of how this will play out if we take the right steps.

That’s as normal as things are going to get for a while.

https://ift.tt/2RwCs7x https://ift.tt/2RqwSDJ